Objectives: The objective of the study was to find the prevalence and pattern of tobacco use, exposure to tobacco prevention activity among adolescent from tribal area. Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in six tribal villages. Data was collected by interview from 240 adolescent by home visits. Results: Prevalence of tobacco use (all forms), smokeless tobacco use and smoking in tribal adolescents were 54.45%, 53.41%, and 23.14%, respectively. Prevalence of tobacco use in boys (66.25%; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 60.29-72.21) was more than girls (26%; 95% CI = 25.84-37.57). Prevalence of tobacco use was more in late adolescent period and earning adolescents. The average age of starting smokeless tobacco use and smoking was 13.75 years (SD 2.26) and 14.22 years (SD 2.54), respectively. Boys start smoking relatively earlier than girls (P = 0.04). Education shows significant protective effect on tobacco use. Bidi was commonly used for smoking, while pan masala and gutka were the preferred smokeless tobacco. Almost all smokers were also using smokeless tobacco. Around 69% adolescents from the tribal area have heard of the tobacco prevention message, but only three could interpret it correctly. Radio and television were the commonest modes of information. Conclusion: Considering the high prevalence of tobacco use among tribal adolescents, anti-tobacco activities need to scale up for tribal people, with more emphasis on behavior change through group or personal approach. School programs may have some limitation in tribal area due to high school dropout, and low enrolment. Prevention activities need more focus on smokeless tobacco use and bidi smoking. Keywords: Adolescent, Smokeless Tobacco, Smoking, Tobacco Prevention, Tobacco use, Tribal Area

At present, an estimated 1.2 billion persons are using tobacco in some form worldwide, which is expected to rise to 1.6 billion by 2020. Tobacco use is attributed for deaths of 3.5 to 4 million people globally, which is expected to increase to about 10 million during 2020 and around more than two-third will be occurring in developing countries as they are showing an increasing trends of tobacco use. [1],[2] By 2010, India had an approximately 120 million smokers.[1] Researchers from India have recognized tobacco use as a major public health problem. Inspite of being the tobacco control initiatives and efforts over 50 years, it is evident from various surveys that the prevalence of tobacco use in India remains relatively unaltered. [3],[4],[5],[6],[7] Study conducted in 2000 shows a very high prevalence of tobacco use in India, ranging from 41 to 50% in men and to 14% in women. [8] National Family Health Survey – 3 (2005 – 2006) reported a prevalence of tobacco use as 57% and 10.5% in men and women, respectively. [9] NFHS 3 has also reported a relatively higher prevalence of tobacco use in rural than in urban area, [9] but in tribal area the prevalence of tobacco use is still very high compared to rural and urban counterpart. [10],[11] However, most of these surveys, except global youth tobacco survey have reported prevalence of tobacco use in a wide range of age group, i.e 15 years and above. There is too little evidence regarding the prevalence and pattern of tobacco use especially among adolescent from tribal area in India. In India, although the community education program and awareness regarding the health hazards of tobacco use seems to have increased during recent times, [3],[12],[13],[14] scaling up of anti-tobacco initiatives to cover entire country, especially the tribal area, with relatively higher prevalence of tobacco use is a huge, but essential task. There are not enough studies that have documented the successful penetration of anti-tobacco messages or programs, if any, in tribal area in Indian setting. Therefore, this study was aimed to find out the prevalence and pattern of tobacco use, exposure to tobacco prevention activity and awareness regarding health hazard of tobacco use in adolescent from tribal area of Wardha district of Maharashtra state of India.

This cross-sectional study was conducted in six tribal villages of Wardha district of Maharashtra state. The total population of villages was 3305 and 738 households (2001 census). The villages are located almost in the forests, and the main occupation is farming and labor work. All selected villages have a school till 4 th grade (primary school). Two of the six selected villages have health sub-center and the average distances of villages from primary health center is around 30 kms. The study participants were adolescent (age group of 11 to 19 years), and included both males and females. House to house visits were done in all selected villages in morning hours. Adolescent, both males and females available in household at the time of survey were included in the study after their consent. Those who were not willing were not interviewed. Out of 271 adolescents available at the time of house visit, 242 gave consent, and were included in the study. Response rate was 89.30%. Confidentiality of the information was assured to them and interview was conducted in a local language. The study protocol was passed by ethics committee. A predesigned structured interview schedule was used to collect data. The schedule was pilot tested prior to data collection. The final schedule consists of questions related to socio-demographic information, tobacco use and its form, exposure to tobacco prevention activities or prevention messages and perceived harmful effects of tobacco use. The schedule had some open space to record the participants verbatim regarding their understanding or interpretation of tobacco prevention activities or messages. Definitions Early adolescent period was defined as age group of 11 to 15 years and late adolescent period was defined as the age group of 15 to 19 years. Smokeless form of tobacco [2],[8],[9] Betelquid is a combination of betel leaf, areca nut, slaked lime, tobacco (optional), catechu and condiments according to individual preferences. Khaini consists of roasted tobacco flakes mixed with slaked lime. This mixture is prepared by the user keeping the ingredients on the left palm and rubbing it with the right thumb. The prepared pinch is kept in the lower labial or buccal sulcus. Mawa is a mixture of areca nut, tobacco, and slaked lime and is chewed. Snuff is a black-brown powder obtained from tobacco through roasting and pulverization. Snuff is used via nasal insufflations. It is also applied on the gum by finger. It is known as bajar and mishri. Gutka is a manufactured smokeless tobacco product (MSTP), a mixture of areca nut, tobacco, and some condiments, marketed in different flavors in colorful pouches. The mixture is chewed and sucked. Pan masala is a betel quid mixture, which contains areca nut and some condiments, but may or may not contain tobacco. The mixture is chewed and sucked. Smoking practices [2],[8],[9] Bidi is a cheap smoking stick, handmade by rolling a dried, rectangular piece of temburni leaf (Diospyros melanaxylon) with 0.15-0.25 g of sun-dried, flaked tobacco filled into a conical shape and the roll is secured with a thread. The length of a bidi varies from 4.0-7.5 cm. Chillum is a conical clay-pipe of about 10 cm long. The narrow end is put inside the mouth, often wrapped in a wet cloth that acts as a filter. This is used to smoke tobacco alone or tobacco mixed with ganja (marijuana). Hooka (a hubble bubble Indian pipe) is an indigenous device, made out of wooden and metallic pipes, used for smoking tobacco. The tobacco smoke passes through water kept in a spherical receptacle, in which some aromatic substances may also be added. Other forms of smoking – Hookli (short clay pipe-like device, being about 7 cm long used for smoking tobacco), Chhutta (coarsely prepared roll of tobacco (cheroot), smoked with the burning end inside the mouth (reverse chhutta smoking), Dhumti is a cigar-like product made by rolling tobacco leaves inside the leaf of jackfruit tree. Analysis The main outcome variables were prevalence and pattern of tobacco use in adolescents from tribal area and exposure of adolescent to tobacco prevention activity and messages. Those who were currently using any form of tobacco were considered for estimating prevalence of tobacco users. For estimating prevalence tobacco user were classified as smokeless tobacco user, smokers and some form of tobacco use (either smoking or smokeless tobacco use or both). Prevalence of tobacco use was compared across various socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. To find out the independent effect of some important predictor on tobacco use, a logistic regression analysis was performed. Verbatim of the respondents regarding their perception of tobacco preventions activities or messages were also considered for studying their interpretation of tobacco prevention messages and their awareness regarding hazards of tobacco.

[Table 1] shows the socio-demographic characteristics of study participants. The mean age was 15.41 (SD 2.41) years. Of the 242 adolescents participated in study, 126 (52.07%; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 46 – 58) were using some form of tobacco. Overall 122 (50.41%; 95% CI = 44 – 57) adolescent were using smokeless tobacco and 56 (23.14%; 95% CI =18 – 28) were current smokers. Adolescents using both forms, smokeless tobacco users as well as smokers, were 52 (21.49; 95% CI = 16-27).

Out of the 160 adolescent boys, 106 (66.25%; 95%CI =60.29 – 72.21) were using some form of tobacco and 26 (31.70%; 95% CI =25.84 – 37.57) out of 82 adolescent girls were using some from of tobacco. The difference was found to be statistically significant (Chi square −7.558; P = 0.006) [Table 1]. Prevalence of tobacco use was significantly more in late adolescents (65.44%) compared to early adolescent period (40.57%) (Chi square −12.579; P = 0.00) and in earning adolescents (63.48%) compared to unemployed and students (50.42%) (Chi square −44.88, df = 2, P = 0.00). Smokeless form of tobacco use was significantly more in adolescent boys (Chi square −8.340, P = 0.004); late adolescent period (Chi square −12.402, P = 0.000) and earning adolescents (Chi square −38.49, df = 2, P = 0.000). Smoking was also found to be significantly more in boys (Chi square −16.481, P?=?0.000), and earning adolescents (Chi square ?16.113 df?=?2, = 0.000), and earning adolescents (Chi square −16.113 df = 2, P = 0.00. Education does not have significant effect on the tobacco use in any form (P > 0.05) [Table 1]. The average age of starting smokeless tobacco use and smoking was 13.75 years (SD 2.26) and 14.22 years (SD 2.54), respectively. Average age of starting the smokeless tobacco in males (13.80 years; SD 2.01) and females (13.61 years; SD 2.87) was not significantly different (t = 0.445, P = 0.657), whereas the mean age of initiation of smoking in adolescent boys (13.11 years; SD 2.43) was significantly less compared to that adolescent girls (14.46 years; SD 2.77) (t = 2.012, P = 0.047). Logistic regression analysis was used to find out the independent effect of predictors on tobacco use. The predictors included in the models were age group, education, occupation, and per-capita income. Late adolescent period was significantly associated with smokeless or some forms of tobacco use. Education shows a significant inverse independent relationship with some form tobacco use and smokeless form of tobacco use. Adolescent those who are earning were using more tobacco compared to students [Table 2].

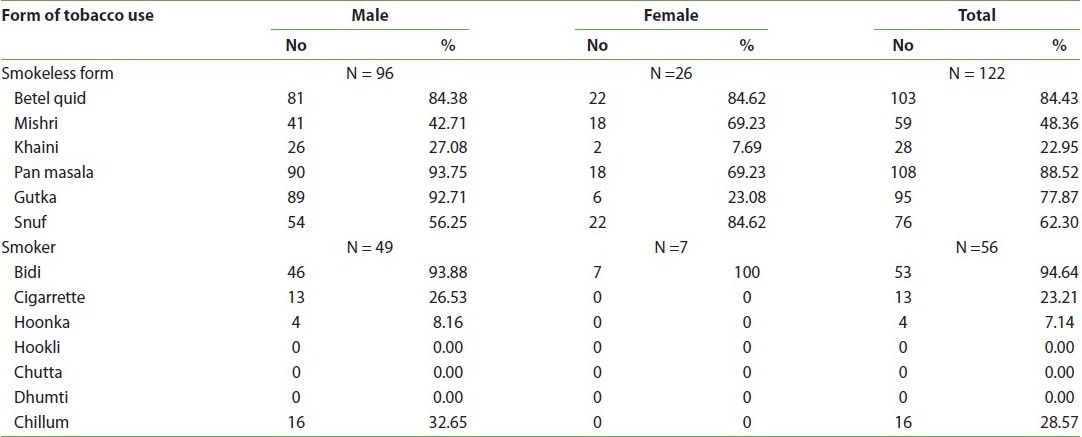

The common reasons for using tobacco were to experiment (64%), influence of family members using tobacco (81%) or friends using tobacco (67%). Initially they started tobacco use irregularly and finally become habitual to tobacco use. The duration from experimental use to habitual use of tobacco ranges from two months to three years. Commonest smokeless tobacco used by tribal adolescents were pan masala (88.52%) followed by betel quid (84.43%). Gutka was consumed by 77.87% adolescents. Snuf and the betel quid were the preferred form of smokeless tobacco among females (84.62%). Bidi’s were most commonly used for smoking by adolescent boys and girls. Other form used by males smokers were cigarette and chillum [Table 3].

Around 69% adolescents from tribal area have heard of the tobacco prevention message, but only three could interpret it correctly. The commonest source of information was radio (73.5%) followed by television (44.31). None of the participant had ever attended tobacco prevention program or event. Neither were they contacted by any NGO and/or persons working for tobacco prevention. Sixty-two adolescents who were aware of warning sign printed over the tobacco packet, but only 13 (20.97%) could interpret it correctly. A significant proportion of adolescents (94.2%) were aware of the hazard of tobacco use, but most of them have either incomplete or incorrect knowledge. The commonest diseases due to tobacco use, as mentioned by them, were cough, tuberculosis, cancer, and asthma.

This study reports, very high prevalence of tobacco use in adolescents from the tribal area. The prevalence of some form of tobacco use in tribal adolescents was 52.07%. The prevalence of tobacco use was significantly more in adolescent boys (66.25%) compared to adolescent girls (23.45%). Global youth tobacco survey [12] reported relatively lower prevalence of 17.5% for any form of tobacco use among 13 to 15 years students compared to our study. NFHS-3 [9] reports the countrywide prevalence of any forms of tobacco use as 57% in men and 10.8% in women in the age group of 13 to 49 years, and in Maharashtra state 48.2% men and 10.5% women in same age group use tobacco. A very high prevalence of smokeless tobacco use among adolescents from tribal area was observed in this study. Almost 50% adolescents were using smokeless tobacco. Prevalence of smokeless tobacco use was significantly more in adolescent boys (60%) compared to girls (31.17%). A study from tribal area of Kerala also reported a very high prevalence of smokeless tobacco use in tribal people, i.e. 65.0% and 24.7% in male and females, respectively, in the age group of 13 to 80 years. [10] Overall prevalence of smoking was 23.14%. The prevalence of smoking was also significantly more in boys (30.63%) as compared to girls (8.54%). NFHS-3 reported nationwide prevalence of smoking in men (32.7%) and women (1.4%) in age group of 13 to 49 years. Study from tribal region of Kerala [10] reports the very high prevalence of 63% for smoking among males, and 1.4% among females in the age group of 13 to 80 years. The higher prevalence of smoking in these studies, compared to our study may be due to wider range of age group and different socio-cultural pattern. The average age of initiation of smokeless tobacco use and smoking was 13.7 years and 14.2 years, respectively. Adolescent boys start tobacco use at relatively younger age compared to girls. A study from rural India reports the mean age for starting tobacco use was 17.2 years. [15] Thus, it seems that adolescents from tribal area start tobacco use at relatively younger age compared to rural area. Nationwide NFHS 3 [9] as well as other studies [10],[11] have clearly documented that the prevalence of tobacco use increases with age. Our study also report a very high prevalence of tobacco use in late adolescent period (65.44%) compared to that in early adolescent period (40.57%). Similarly those who have some earning were using more tobacco compared to those who were not earning or studying. In this study most of the earning adolescents were in late adolescent period. Therefore, increased prevalence in this subgroup could be attributed to having money to purchase tobacco products and more exposure to peers using tobacco. Other reason could be that in tribal area tobacco use is a part of the custom or traditions [10],[11] and late adolescent is considered to be grown up to use tobacco in some form. A study conducted in rural India have also reported that age and occupation had significant association with tobacco use. [15] Overall, it was observed that around 55% adolescents were attending school at the time of survey. Almost 67% adolescents who were out of school at the time of survey were using tobacco in some form. On logistic regression analysis, schooling showed significant protective effect on tobacco use, particularly with smokeless form. Studies from tribal [10] and rural [16],[17] parts of India also report that tobacco use is inversely related to education. NFHS-3 [9] also reports that prevalence of tobacco use was more in non educated men (78%) and women (18%). Late adolescent period and earning adolescents have a significant independent effect on smoke-less tobacco use but for smoking, only earning shows the significant independent association on logistic regression analysis. The variety of forms of tobacco use is unique to India. Apart from the smoked forms that include bidis, cigarettes, and cigars, a plethora of smokeless forms of consumption exist and they account for about 35% of the total tobacco consumption. [3],[4],[18] A very typical pattern of the tobacco use was observed in our study. Almost all smokers were also using the smokeless form of tobacco; moreover, initially they started with smokeless form and then slowly graduated to smoking. Pan masala, betel quid, and gutka were commonly used smokeless tobacco. Bidis was commonly used for smoking as it was locally available and cheaper. Almost similar findings were reported by a study from coastal Kerala and NFHS-3 survey and studies from tribal India. [9],[1]0,[11],[17] The bidi is often called the poor man’s cigarette and is perhaps the cheapest tobacco smoking product in the world, costing about a one-third of one U.S. cent in India. Bidi smoking is associated with the diseases caused by cigarette smoking and results in similar physiological changes. [19],[20] A bidi contains about one-fourth the quantity of tobacco as a cigarette yet it delivers a higher amount of tar and nicotine. Just like cigarette smoking, bidi smoking has been shown to increase the risk of chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis, and respiratory diseases. In India, mortality rates among bidi smokers were reported to be significantly higher compared to smokeless tobacco users or non tobacco users. [19],[21] Traditionally, tobacco control programs have focused on reducing cigarette smoking. Effective strategies are now needed to expand the focus of tobacco control programs to all types of tobacco use, including all smokeless forms and bidis. [19] Various studies from tribal India reports that socio-cultural customs in the tribes, peer pressure, work relief, pleasure, remedy for toothache are the common reason for starting tobacco use. [10],[11] Tobacco is also a socio-culturally accepted in tribal part of India. [10],[11] In this study, social factors and influence of family member using tobacco emerged out to be an important reason for using tobacco. A typical finding was that adolescent used tobacco for the first time just to experiment, as either their family member or friends were using it. Then gradually started using tobacco irregularly and finally become habitual tobacco user. However, we could not get the consistent reasons regarding the duration of change in practice, i.e. from experimental tobacco use to regular user, either the due to recall bias or due to different interpretations of habitual tobacco use by study participants. Over the past 50 years, clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory studies have clearly shown that tobacco use is a major etiological factor in a number of disabling and fatal diseases. Surprisingly, more than ninety percent adolescents were aware of the hazard of tobacco use, but most of them have either incomplete or incorrect knowledge. Adolescents mentioned that cough, tuberculosis, cancer, and asthma are the common disease caused by tobacco use. Surprisingly, oral cancer was mentioned by only 20% adolescents. Moreover, they attributed oral cancer to only gutka use and not other form of tobacco. It is a formidable challenge to convince adolescents from tribal area about the role of tobacco in causing these diseases as the ill effects of tobacco manifest only after a period of years and are thus not obviously linked to habit. [16],[19] Studies from rural India reported that illiteracy was associated with greater unawareness of the ill effects of tobacco use. [16] It was obvious from this study that the problem related to tobacco use was most acute in tribal area as vast number of adolescent from tribal area use some form of tobacco compared to rural and urban counterparts, therefore we studied the penetration of tobacco prevention programs and messages in tribal villages. Not a single adolescent participated in our study have never attended program or training or workshop on tobacco prevention nor they were contacted by any NGO and/or persons working for tobacco control. With regard to awareness of statutory warning message to be printed on tobacco packet, two third were aware of it but only one fifth of them could interpret it correctly. Mass media is commonly used to spread awareness regarding hazards of tobacco use, as it is cost-effective and have a wider reach. In mass approach, sources used to deliver information also play an important role. [20] In our study area, radio and television were the commonest sources of information. However, mass media approach has its inherent limitation. It is the one way communication and moreover it is effective in the beginning, particularly in making people aware of the problem and getting them to worry about it, but personal or group approach become progressively more important in the later stages. [20] In personal or group approach adolescents may get their queries or concerns addressed. This was also clearly supported by our study findings that more than ninety percent adolescent knew some tobacco related hazard, but either they have incorrect or incomplete knowledge. India’s Tobacco prevention initiatives as well as National Tobacco Control Cell give importance to tobacco prevention activities in the schools and colleges. Tobacco is been included as a topic in school curriculum in India. [4],[18] All six tribal villages that we have included in our study have school up to 4 grades only. Giving tobacco prevention messages in 4 th grade, where the average age of students will be around 9 years, may be too early. Moreover, the average age of tobacco use in our study was over 14 years. Other limitation of this strategy for tobacco prevention is the low school enrolment or early school dropouts in tribal area. Our study also shows that around 50% of the adolescent were out of school. Thus, tribal region needs mix of approaches/strategies to tackle tobacco-related problem. This study had some limitations. We have not studied the effects/hazards of tobacco use in tribal adolescents. Other studies that we have discussed were conducted on people mostly over 13 years of age and moreover, they were conducted in rural or urban settings, except two nationwide surveys (NFHS 2 and 3) and two studies were from tribal area. However, we deliberately compared the findings from urban or rural population above 13 years of age with findings from our study (i.e., on tribal adolescents) to get a comparative idea of prevalence of tobacco use in tribal adolescent, compared to their urban or rural counterparts. It was obvious that the prevalence was quite high in our study area among adolescent, compared to urban or rural area. To conclude, given the very high prevalence smoking and smokeless form of tobacco use among adolescent from tribal areas, anti-tobacco awareness programs targeting tribal areas need to be scaled up. The prevention activity needs to focus on behavior change through group or personal approach rather than just giving information through mass approach. Prevention activities also need more focus on smokeless form of tobacco use and bidi smoking. Capacity building of local NGOs can be done to support the tobacco control programs for tribal people of India. School intervention programs may have some limitation due to low enrolment and early school dropout in tribal area. Other activities may range from developing, community education, organizing events, competitions, and skill building workshops, etc., however such programs must be sensitive to the socio-cultural practices of tribal people.

DOI: 10.4103/1755-6783.85756

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||