|

Tuberculosis is common in India but tubercular breast abscess still remainsa rare entity. This paradox exists due to misdiagnosis and underreporting. A high index of suspicion is required in diagnosing the condition which mimics pyogenic abscess or benign breast disease. We present a case of a 21-year-old college student who presented to surgical OPD with lump in right breast. Prolonged treatment with antibiotics did not show any clinical response. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) performed on the pus indicated the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Only repeated Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) revealed acid-fast bacilli. Antitubercular therapy was initiated with favorable clinical response.

Keywords: Breast, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, polymerase chain reaction

How to cite this article:

Lall M, Sahni A K. Polymerase chain reaction: The panacea for diagnosing tubercular breast disease?. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2013;6:131-3 |

How to cite this URL:

Lall M, Sahni A K. Polymerase chain reaction: The panacea for diagnosing tubercular breast disease?. Ann Trop Med Public Health [serial online] 2013 [cited 2016 Aug 15];6:131-3. Available from: https://www.atmph.org/text.asp?2013/6/1/131/115192 |

Breast tuberculosis is a rare form of tuberculosis. [1],[2] The high resistance offered by the breast tissue to the survival and multiplication of tubercle bacilli has been postulated to be the cause of the rarity of breast tuberculosis. [3] Breast tuberculosis is most commonly present as a lump. [4] The most common mode of presentation, especially in young women, is in the form of a breast abscess. [5] Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is the diagnostic modality; however, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the diagnosis of breast tuberculosis is less often reported and only in selected reports. [6] We highlight the diagnostic importance of PCR in early detection of breast abscess of tubercular origin at centers where facilities exist. A case of secondary breast abscess diagnosed early with the help of PCR is presented.

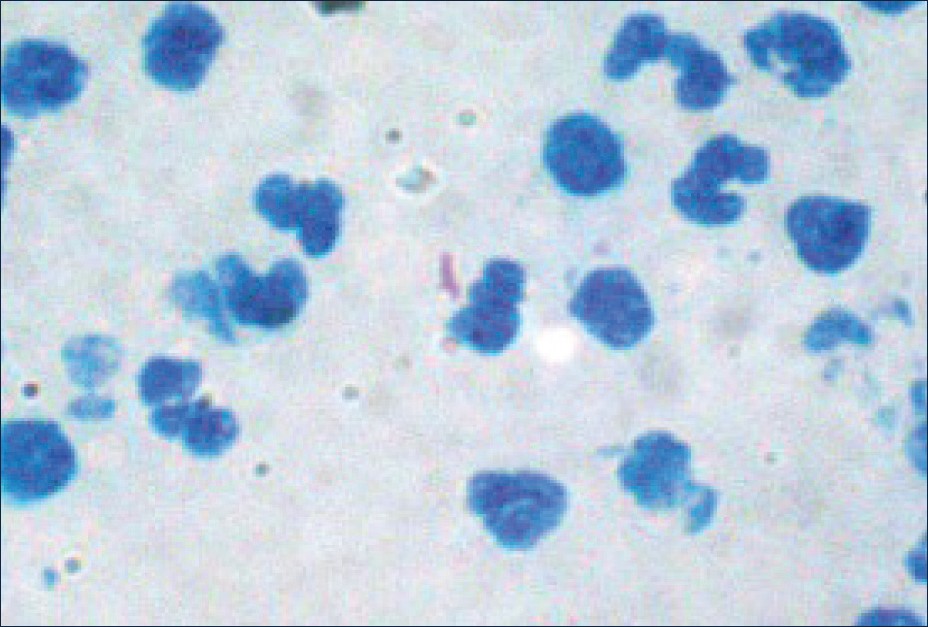

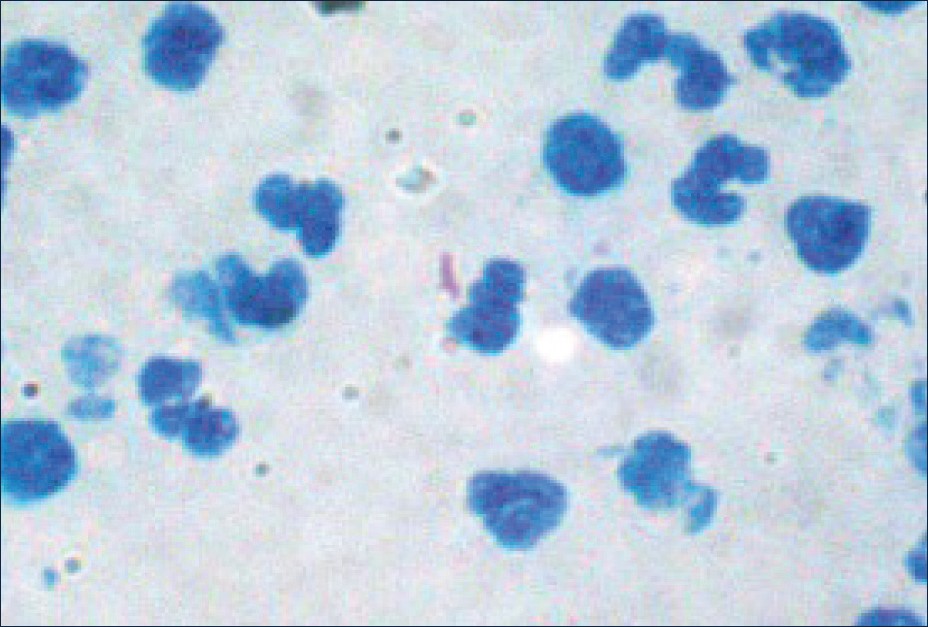

A 21-year-old unmarried girl presented with a painless lump in her right breast of 3 months duration. There was no history of discharge from the nipple. Physical examination revealed a 4 cm mobile firm mass in the central quadrant of the breast. Overlying skin was normal with no signs of inflammation. Nipple and areola appeared normal. A 1.5 cm lymph node was found in the right axilla which was painless and mobile. X-ray chest revealed nonhomogeneous opacities in the right lung. Her leucocyte count was 11,000 mm 3 with 68% neutrophils; Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 60 mm at the end of 1 hr. HIV status was negative. Fine needle aspiration was performed from the breast lump under palpation, yielding a small amount of pus-like material. Cytological examination revealed numerous degenerated neutrophils and lymphocytes in a dirty background with a few epitheloid cells and giant cells. Gram stain of the pus showed gram-positive cocci in clusters. Pus culture on routine bacteriological media grew colonies of Staphylococcus aureus. A diagnosis of pyogenic abscess was done, and the patient was given a course of antibiotics. However, she did not respond to the prolonged course of antibiotics, and a second FNAC was asked with culture and PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Gram stain of the pus showed many polymorphs and weakly staining gram-positive structures. Ziehl Neelsen (ZN) stain of the aspirate revealed acid-fast bacilli on amidst a background of fair number of pus cells [Figure 1]. PCR using primers for mpb64 protein-coding gene yielded a positive result [Figure 2].

|

Figure 1: Breast aspirate showing acid fast bacilli lying in a pair

Click here to view |

|

Figure 2: PCR amplification of mpb64 gene of M. tuberculosis on 1.5% agarose gel. M- molecular weight marker, lane 1-Negative control, lane 2-Test sample, lane 3-Negative sample, lane 4- Positive control

Click here to view |

Breast tuberculosis is rare in the western countries, occurring in <0.1% of the breast lesions examined histologically; however, it could show resurgence with the AIDS pandemic. The overall incidence in developing countries is approximately 3.0% of all surgically treated breast disease. [7] Tuberculosis of the breast is a disease of women aged between 20 and 50 years though it may affect males too. Mammary tuberculosis may be primary, when no demonstrable tuberculous focus exists elsewhere in the body, or secondary to a pre-existing lesion located elsewhere in the body. Primary tuberculosis of the breast may occur through skin abrasions or through the milk duct openings on the nipple. [8],[9],[10] However, it is generally believed that tuberculous infection of the breast is usually secondary to a pre-existing tuberculous focus located elsewhere in the body. Such a pre-existing focus could be of pulmonary origin or could be a lymph node within the paratracheal, internal mammary, or axillary nodal basins. Involvement of the breast in such cases of secondary tuberculous infection is presumed to be by direct hematogenous spread. However, the more accepted view for spread of the infection is centripetal lymphatic spread, communication between the axillary glands, and the breast resulting in secondary involvement of the breast by retrograde lymphatic extension. Supporting this hypothesis is the observation of axillary node involvement in 50-75% of cases of tubercular mastitis. [11] In our patient also, there was a right axillary lymph node associated with the right breast lesion. Direct extension from contiguous structures such as the underlying ribs is another possible mode of infection, as previously reported by Eroðlu et al . [12] Chest radiographs revealed nonhomogeneous opacities in the lung suggestive of pulmonary tuberculosis. In this particular case, she possibly had a secondary tuberculous infection. The accurate diagnosis of mammary tuberculosis has traditionally relied upon the demonstration of a classical caseous lesion, acid-fast bacilli within such a lesion, and/or the demonstration of epitheloid granulomas, Langhans’ giant cells, and lymphocytic aggregates. [13] There are reports of PCR as a diagnostic tool for rapid identification of M. tuberculosis in cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. [14] Performance of PCR has been studied in smear positive and negative non-respiratory samples and sensitivity rates reported as up to 90% in extrapulmonary tuberculosis. [15] In our case, PCR proved to provide a very rapid diagnosis. Differentiation of M. tuberculosis from other Mycobacteria species represents an important diagnostic issue and false positive results have to be kept in mind. Inclusion of appropriate positive and negative controls ensures internal quality control and standardization of the assay.

Breast tuberculosis is commonly present as an acute abscess resulting from infection of the area of tuberculosis by pyogenic organisms. [16] This results in the disease being overlooked and misdiagnosed as pyogenic abscess or benign breast disease as that occurred in our patient. Multiple needle aspirations and repeated microbiological examinations are required to diagnose these cases.

Mammary tuberculosis is not a very commonly diagnosed condition. Despite modern imaging techniques, differentiation from other benign or malignant conditions can be difficult. The most reliable and definitive diagnostic techniques include culture of aspirate and histological examination of the tissue sample. Molecular techniques have revolutionized the diagnosis of tuberculosis and should be relied upon where facilities exist. They, however, neither replace nor reduce the need for conventional smear and culture, which remain the gold standard for the diagnosis of this uncommon condition.

| 1. |

Kalac N, Ozkan B, Dursun AB, Demirag F. Breast tuberculosis. Breast 2002;11:346-9. |

| 2. |

Kakkar S, Kapila K, Singh MK, Verma K. Tuberculosis of the breast. A cytomorphologic study. Acta Cytol 2000;44:292-6. |

| 3. |

Mohan A, Sharma SK. Tuberculosis at other body sites. In: Sharma SK, Mohan A, editors. Tuberculosis. 1 st ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2001. p. 607. |

| 4. |

Alagaratnam TT, Ong GB. Tuberculosis of the breast. Br J Surg 1980;67:125-6. |

| 5. |

Tewari M, Shukla HS. Breast tuberculosis: Diagnosis, clinical features & management. Indian J Med Res 2005;122:103-10. |

| 6. |

Tse GM, Poon CS, Ramachandram K, Ma TK, Pang LM, Law BK, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: A clinicopathological review of 26 cases. Pathology 2004;36:254-7. |

| 7. |

Gupta PP, Gupta KB. Tuberculous mastitis: A review of seven consecutive cases. Indian J Tuberc 2003;50:47. |

| 8. |

Shinde SR, Chandawarkar RY, Deshmukh SP. Tuberculosis of the breast masquerading as carcinoma: A study of 100 patients. World J Surg 1995;19:379-81. |

| 9. |

Harris SH, Khan MA, Khan R, Haque F, Syed A, Ansari MM. Mammary tuberculosis: Analysis of thirty-eight patients. ANZ J Surg 2006;76:234 – 7. |

| 10. |

Göksoy E, Düren M, Durgun V, Uygun N. Tuberculosis of the breast. Eur J Surg 1995;161:471 – 3. |

| 11. |

Sharma PK, Babel AL, Yadav SS. Tuberculosis of breast (study of 7 cases). J Postgrad Med 1991;37:24-6. |

| 12. |

Eroðlu A, Kürkçüoðlu C, Karaoðlanoðlu N, Kaynar H. Breast mass caused by rib tuberculosis abscess. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;22:324-6. |

| 13. |

Khanna R, Prasanna GV, Gupta P, Kumar M, Khanna S, Khanna AK. Mammary tuberculosis: Report on 52 cases. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:422-4. |

| 14. |

Lily K, Jayanthi U, Madhavan HN. Application of nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) using MPB64 gene primers to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in clinical specimens from extra pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Indian J Med Res 2005;122:165-70. |

| 15. |

Gomez P, Moris SL, Panduro A. Rapid and efficient detection of extrapulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis by PCR analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000;4:361-70. |

| 16. |

Dixon JM. Breast infection: ABC of breast diseases. BMJ 1994;309:946. |

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

DOI: 10.4103/1755-6783.115192

[Figure 1], [Figure 2] |