| Abstract |

Fasciolopsiasis is a disease caused by Fasciolopsis buski where humans acquire the infection by consumption of raw fresh water plants contaminated with metacercariae stage of the parasite. We are reporting an unusual case, in which an 11-year-old boy vomited out 4 live adult worms. The patient had complains of occasional gastrointestinal symptoms. The worms were identified as F. buski based on gross morphology and histopathological examination. The stool sample examination also revealed the presence of eggs of F. buski. The patient was successfully treated with nitazoxanide. Finding of live adult worms in the vomitus of a child in a non-endemic area is extremely rare and raises the possibility of unidentified cases in this region

Keywords: Fasciolopsis buski , nitazoxanide, vomitus

| How to cite this article: Mohanty I, Narasimham M V, Sahu S, Panda P, Parida B. Live Fasciolopsis buski vomited out by a boy. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2012;5:403-5 |

| How to cite this URL: Mohanty I, Narasimham M V, Sahu S, Panda P, Parida B. Live Fasciolopsis buski vomited out by a boy. Ann Trop Med Public Health [serial online] 2012 [cited 2020 Aug 8];5:403-5. Available from: https://www.atmph.org/text.asp?2012/5/4/403/102092 |

| Introduction |

Facsiolopsis buski, also called as giant fluke, is the largest intestinal fluke parasitizing humans. It is a duodenal digenetic trematode of the Fasciolidae family. The fluke was first described by Busk in 1943 in the duodenum of an Indian sailor who died in London. [1] Fasciolopsiasis is seen in various parts of South-east Asia including China, Taiwan, Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, and Thailand. [2]

The adult worm is found attached to the mucosa of the duodenum and jejunum of pig and man. Adult worm lays unembryonated eggs, which are excreted out in the faces and undergo further development in water. A ciliated miracidium develops inside the egg and comes out in about 3 to 4 weeks and penetrates a suitable snail host. Asexual multiplication takes place inside the snail to form a large number of cercariae. Free-swimming cercariae emerge from the snail and encyst to metacercariae on the surface of aquatic plants. Man gets infected on ingestion of these parasitized plants, and the cycle is repeated. Most infections in man are asymptomatic. [3] In cases of severe infection, prominent clinical signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, low-grade fever, and generalized edema may be seen. Diagnosis is made by detecting eggs in stool, but the distinction between Fasciolopsis buski and Fasciola hepatica is very difficult to make in routine stool examinations. [4] We report an unusual case of Fasciolopsiasis, in which the adult worms were passed out in the vomitus of an 11-year-old boy.

| Case Report |

An 11-year-old boy vomited out 4 live leaf-shaped fleshy worms in the morning after getting up from the bed. His parents took the expelled worms to the pediatrician, which were referred to the department of microbiology for identification. The boy had no specific symptoms prior to this, except occasional abdominal discomfort, nausea, and mild distension. He had also been prescribed albendazole 400 mg single dose by the local physician without any investigations.

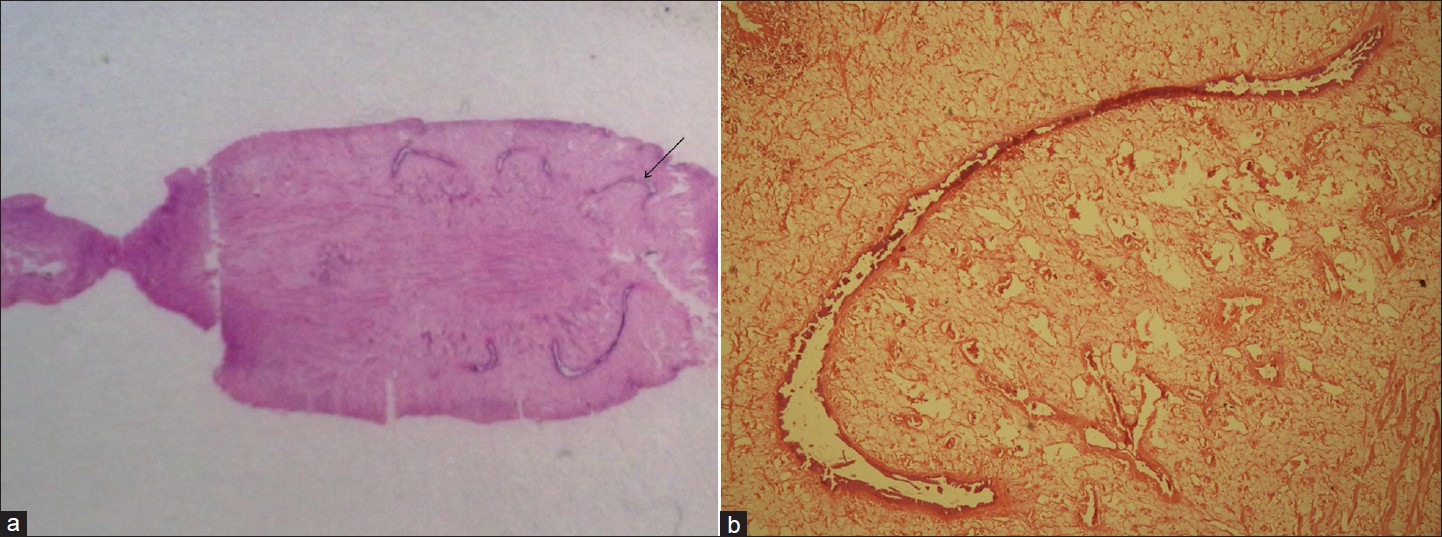

A single worm was sent in a bottle containing normal saline for identification. It was then transferred to a Petri dish More Details for examination. The worm was dorsoventrally flattened, non-segmented, and flesh- colored. It measured about 34 mm x 20 mm in size. The other worms were nearly of the same size as reported by the father of the boy. Two suckers were seen; ventral and oral, and the ventral sucker was relatively prominent about 2 mm in size. The worm was fleshy and nearly oval in shape with the anterior end narrower and the posterior end broadly rounded. There was no cephalic cone present [Figure 1] and b. The morphology of the worm resembled Fasciolopsis buski. Histopathological examination of the worm showed that the intestinal caeca was unbranched. Stool examination revealed the presence of bile stained, operculated eggs about 130 x 80 μm in size. The worm was identified as F. buski based on the morphology of the adult worm, absence of cephalic cone, and HP section showing unbranched intestinal caeca [Figure 2]a and b.

| Figure 1: (a) Photograph showing dorsal view of the adult worm, (b) Photograph showing ventral view of the adult worm |

|

Figure 2: (a) Close view of the HP section of the adult worm, (b) HP section of the adult worm showing unbranched intestinal caeca (H and E, 400x) |

Routine laboratory investigations revealed Hb 10.6 gm%, TLC 9400/cu mm, Differential count: P-68, L 24, E 8, and ESR 34 mm/hr. There was no history of travelling. The boy was treated with nitazoxanide 250 mg twice-daily for 5 days. After 2 weeks of treatment, stool samples were examined but did not show any evidence of any parasite or ova.

| Discussion |

F. buski infestation has been reported in India mainly from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Maharashtra and sporadically from other states like Assam and West Bengal. [5] It is usually seen in rural areas where water plants are eaten raw. This patient belongs to village in southern district of Odisha where water scarcity prevails throughout the year and the people have to depend on pond water for their daily needs. The patient also gave history of consumption of water chestnuts. He had occasional mild gastrointestinal symptoms, for which he was given albendazole as a dewormin. As most cases of Fasciolposiasis are asymptomatic, high degree of suspicion is required for diagnosis in a non-endemic area like ours. Most human cases of F. buski infestation are diagnosed by identifying egg stage in stool. Adult worms are very rarely seen, except in autopsy, but there is only one case report of live adult worms being vomited out and another report of live adult worms coming out through an ileostomy opening. [5],[6] To the best our knowledge, there are no reports of fasciolopsiasis from this region. This case raises the possibility that there may be more number of unidentified cases in this region. Hence, all children with gastrointestinal symptoms should be screened for parasites before being prescribed dewormin.

| Conclusion |

As the disease is prevalent among children and in people living in endemic areas, this case of fasciolopsiasis from an area that is completely non-endemic raises a need for surveillance in this area, which may help in identifying more undetected cases, if present. Public education about hygiene and control measures must be implicated including measures such as the proper cleaning and processing of vegetables and water plants. The medical personnel in these non-endemic areas should be sensitized about the emerging infection so that adequate control measures can be taken.

| References |

| 1. | Chi Hiong UGo, Bruke AC. Intestinal flukes. website: Available from http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic 1177.htm. [Last cited on 2007 May 14]. |

| 2. | Bhattacharjee HK, Yadav D, Bagga D. Fasciolopsiasis presenting as intestinal perforation: Acase report. Trop Gastroenterol 2009;30:40-1. |

| 3. | Chandra SS. A field study on the clinical aspects of Fasciolopsis buski infection in Uttar Pradesh. Med J Armed Force India 1976;32:181. |

| 4. | Rohela M, Jamaiah I, Menon J, Rachel J. Fasciolopsiasis: A first case report from Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2005;36:2;456-8. |

| 5. | Mahajan RK, Duggal S, Biswas NK, Duggal N, Hans C. A finding of live Fasciolopsis buski in an ileostomy opening. J Infect Dev Ctries 2010;4:401-3. |

| 6. | Le TH, Nguyen VD, Phan BU, Blair D, McManus DP. Case Report: Unusual presentation of Fasciolopsis buski in a Vietnamese child. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2004;98:193-4. |

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

| Check |

DOI: 10.4103/1755-6783.102092

| Figures |