| Abstract |

Escherichia coli (E. coli) was isolated from the pleural space of two patients; the first one was a 32-year-old Nepali man who was healthy before, presented with 15 day fever and cough. Chest x-ray showed left-sided pleural effusion. After diagnostic workup, he was diagnosed to have E. coli parapneumonic empyema. In addition to the antibiotics and intrapleural streptokinase, decortication was required to improve his condition. The second patient was a 61-year-old Egyptian man who was presented with one-week fever with shortness of breath. He had a history of liver cirrhosis with multiple admissions for decompensated liver diseases. Chest x-ray showed right-sided massive pleural effusion. He was diagnosed with spontaneous bacterial empyema. The patient responded well to fluid drainage and administration of antibiotics; the pleural fluid decreased to minimum in 14 days.

Keywords: Escherichia coli , hepatic hydrothorax, parapneumonic empyema, spontaneous bacterial empyema, thoracic empyema

| How to cite this article: Khan FY. Escherichia coli pleural empyema: Two case reports and literature review. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2011;4:128-32 |

| How to cite this URL: Khan FY. Escherichia coli pleural empyema: Two case reports and literature review. Ann Trop Med Public Health [serial online] 2011 [cited 2020 Aug 7];4:128-32. Available from: https://www.atmph.org/text.asp?2011/4/2/128/85770 |

| Introduction |

Escherichia More Details coli is a Gram-negative bacillus; it is facultatively anaerobic with both fermentative and respiratory type of metabolism. E. coli is one of the most frequent causative agents of some of the many common bacterial infections, including cholecystitis, bacteremia, cholangitis, urinary tract infection (UTI), and traveler’s diarrhea, and other infrequent clinical infections such as pneumonia. E. coli is a major facultative inhabitant of the large intestine. Isolation of E. coli from pleural space is uncommon; it occurs in parapneumonic empyema, [1] colopleural fistula empyema, [2] or spontaneous bacterial empyema (SBEM). [3] In this report, we presented two cases of E. coli pleural empyema; one due to parapneumonic empyema, while the other caused by SBEM.

| Case Reports |

Case 1

A 32-year-old Nepali man admitted to our hospital with 15-day fever and cough. One week before admission, he began experiencing left pleuritic chest pain and shortness of breath. He did not have any significant medical history. He had been well and denied any infectious diseases contacts or alcohol abuse. Upon physical examination, his pulse rate was 98/min, respiratory rate was 25/minute, blood pressure was 110/60 mmHg, and temperature was 39.8°C. Chest examination showed left pleural effusion, whereas other examinations were unremarkable. The white blood cell (WBC) count was 19 100/μl (89.7% neutrophils, 3.8% lymphocytes), hemoglobin was 12 g/ dl, and platelets were 378 000/μl. Serum creatinine was 116 μmol/l, alanine aminotransferase was 83 IU/l, and aspartate aminotransferase was 52 IU/l. Chest x-ray showed a left-sided pleural effusion. The patient was treated empirically as parapneumonic effusion with intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone plus azithromycin.

Thoracentesis was carried out, and yielded a purulent and thick fluid (consistent with empyema) with the following characteristics: PH, 6.8; glucose, 0.4 mmol/l; protein, 6.8 g/dl; lactate dehydrogenase, 1 877 IU/l; and WBC count, 3 360/μl (98% neutrophils). A thoracostomy tube was inserted in the pleural space and 1 500 ml of turbid fluid was drained.

Two days later, pleural fluid culture yielded E. coli, which was sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanate, whereas blood, sputum, and urine cultures were negative. Antibiotic therapy was adjusted to IV amoxicillin/clavulanate, 1.2 g every 8 hours. Pleural fluid study for acid fast bacilli (AFB) and cytology was negative. A tuberculin skin test and sputum for AFB were negative.

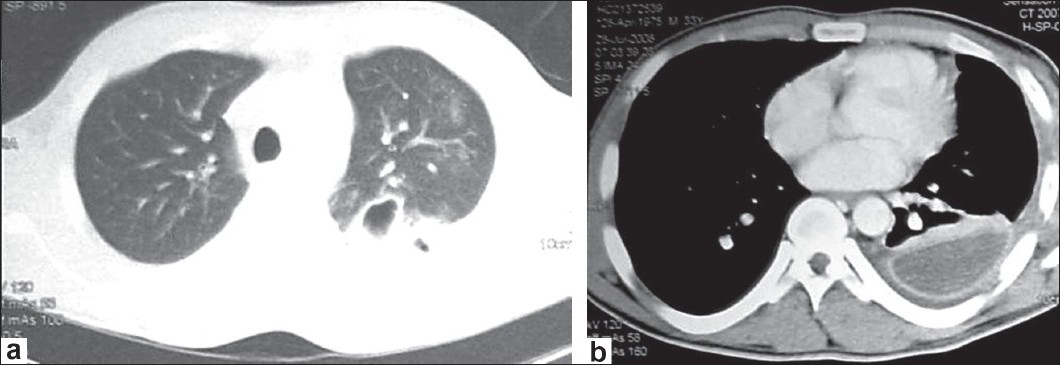

On seventh hospitalization day, the patient continued to have fever and shortness of breath despite antibiotics and fluid drainage. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast showed extensive left-sided pleural effusion with enhancement of the pleura and multiple mediastinal lymph nodes. In addition, there was air containing cavity within the posterior segment of the upper lobe [Figure 1]a. Because the CT findings were also consistent with pulmonary tuberculosis, the pulmonologist was consulted on the same day; he bronchoscoped the patient and performed bronchial wash. On the next days, bronchial wash yielded E. coli which was sensitive to amoxicillin/clavulanate. The patient was kept on the same antibiotic. Twelve days after admission, the fever continued and a control chest CT showed empyema with thick enhancing wall and septations [Figure 1]b. Intrapleural streptokinase was started for 3 days, but fever continued.

|

Figure 1: (a) Chest CT shows air containing cavity within the posterior segment of the upper lobe; (b) CT with contrast shows empyema with thick enhancing wall and septation

Click here to view |

Based on this information, chest surgeon was consulted and left lung decortication was carried out. On the following days, the fever subsided and the patient was kept on the same antibiotic for one week more, after which he was discharged in good condition.

Case 2

A 61-year-old Egyptian man admitted with one-week fever, shortness of breath, and sleep disturbance.

He had hepatitis C virus complicated by liver cirrhosis with multiple admissions for decompensated liver diseases. Upon examination, patient was dyspnic, conscious, and oriented with flapping tremor. Pulse rate was 110/minute, blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg, respiratory rate was 30/minute, and temperature was 38.6°C. Chest examination showed right pleural effusion, whereas abdominal examination revealed ascites. WBC count was 17 900/μl, hemoglobin was 9.3 g/dl, and platelet count was 81 000/μl. Urea nitrogen was 12.3 mmol/l, creatinine: 133 μmol/l, total bilirubin: 36 μmol/l, alkaline phosphatase: 196 IU/l, aspartate aminotransferase: 28 U/l, alanine aminotransferase: 31 U/l, protein: 6.6 g/dl, and albumin: 2.6 g/dl. International normalized ratio was 1.3. Chest x-ray showed right-sided massive pleural effusion [Figure 2]a, while abdominal ultrasonography revealed liver cirrhosis, splenomegaly, and mild ascites with massive right-sided pleural effusion. CT of chest did not demonstrate any pulmonary parenchymal pathology [Figure 2]b.

| Figure 2: (a) Chest x-ray shows massive right-sided effusion; (b) Chest CT shows right-sided effusion without pulmonary parenchymal pathology

Click here to view |

Diagnostic thoracentesis and paracentesis were performed. Ascitic fluid was transparent; WBC count was 1 180/mm 3 (84% neutrophils); Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 332 U/l; total protein, 1.4 g/dl; and albumin, 0.9 g/dl. The leukocyte number was 1 860/μl (65% neutrophils); LDH, 221 U/l; total protein, 2.5 g/dl; and albumin, 0.12 g/dl. Because of massive and symptomatic pleural effusion, the fluid was drained through a pigtail tube. The patient was diagnosed with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and hepatic encephalopathy. IV ceftriaxone with oral lactulose and enema were initiated.

On the following days, blood, sputum, ascitic fluid, and urine cultures were negative, whereas pleural fluid culture yielded E. coli. The microorganism was extended spectrum beta-lactamase and was susceptible for amikacin, tazocin (piperacillin-tazobactam), and meropenem. Pleural and ascitic fluid study for AFB and cytology was negative. A tuberculin skin test and sputum for AFB were negative. The patient was diagnosed to have SBEM. Meropenem was initiated at 1 g every 8 hours for 10 days; during this period, the fever and shortness of breath subsided and a control chest x-ray showed minimal pleural fluid. The patient was discharged after 14 days of hospitalization with spironolactone 75 mg daily and propranolol 80 mg once daily.

| Discussion |

Isolation of E. coli from pleural space is uncommon; it occurs in parapneumonic empyema, colopleural fistula empyema, or SBEM. Parapneumonic effusion is a pleural effusion associated with pneumonia and resulting from an increase in the permeability of the visceral pleura due to inflammation. [4] Parapneumonic effusions occur in about 40 to 57% of cases of bacterial pneumonias. [4],[5],[6] Most effusions are small and are resolved by effectively treating underlying pulmonary infections. However, 10 to 20% of patients develop a complicated parapneumonic effusion or pleural empyema, in which the fluid becomes more exudative and usually requires more aggressive therapy. [7] The bacteriology of pleural effusions is diverse; in the past, aerobic Gram-positive organisms (especially Streptococcus species) have been the most frequent isolates. However, commonly identified bacteria in the infected pleural effusion have changed over recent decades. Gram-negative aerobic bacteria are emerging as important pathogens in cases of parapneumonic effusion or empyema. Nowadays, E. coli, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and Haemophilus influenzae are the most commonly identified Gram-negative bacteria. [8]

Pneumonias due to E. coli are uncommon and are usually hospital-acquired, accounting for 9% of cases reported. [9] On the other hand, E. coli pneumonias can also be community-acquired in patients who have underlying disease such as diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and E. coli UTI; [10] in some reports, 1.2 to 1.6% of the community-acquired pneumonias (CAP) are caused by E. coli,[11],[12] of which 10% were young, healthy individuals. [12] Patient described in case 1 was immunocompetent with no chronic illness before and he denied alcohol abuse.

The organism may reach the respiratory tract by aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions due to colonization or by hematogenous dissemination from a primary source in the gastrointestinal tract or the genitourinary tract. [13] In this patient, blood and urine cultures were negative, which made the possibility of aspirating oropharyngeal secretions most likely. Sputum culture is usually positive in bacteremic form of E. coli pneumonia. [9] In this patient, the pleural fluid and bronchial wash yielded E. coli, while sputum and blood cultures were negative.

E. coli pneumonia usually manifests as a bronchopneumonia of the lower lobes, but the process can be roentgenographically variable [13] and may be complicated by empyema which usually requires more aggressive therapy. In this patient, the posterior segment of the upper lobe was involved and the patient did not respond to antibiotics and intrapleural streptokinase. Lung decortication was needed to improve patient’s condition. In hospital, mortality associated with E. coli pneumonia is varied. In the past, it ranged between 30 and 49%, [13],[14] whereas in recent studies, it ranged between 0 and 10.3%. [12],[15] The most likely reason for this difference in mortality is the current approach to the empirical treatment of CAP.

The above described patient was discharged in good condition.

Hepatic hydrothorax is defined as pleural effusion in a cirrhotic patient without primary pulmonary or cardiac disease. It is a recognized complication of portal hypertension with an estimated prevalence of 5 to 10% in patients with liver cirrhosis. It is usually right-sided but may be left-sided or bilateral. [16] In patients with hepatic hydrothorax, ascites is usually evident but a pleural effusion may develop in a cirrhotic patient in the absence of detectable ascites. [17]

SBEM is an infection of a pre-existing hydrothorax in cirrhotic patients. [18] It accounts for 13 to 30% of the hospitalized cases of hepatic hydrothorax. [19],[20] The causative microorganisms in most cases of SBEM are E. coli, Streptococcus species, Enterococcus species, and Klebsiella species. [21]

The pathogenesis of SBEM remains unclear. The proposed mechanisms include direct bacterial spread from the peritoneal cavity to the pleural cavity. However, it was reported that nearly 40% of the SBEM episodes were not associated with SBP. [18] Moreover, SBEM may occur even in the absence of ascites. [22] In such cases, a transient bacteremia that infects the pleural space could be the underlying pathogenetic mechanism. [20] The patient described in case 2 fulfilled the criteria of culture-negative SBP; thus, direct bacterial spread from the peritoneal cavity to the pleural cavity is the possible mechanism of SBEM in this patient.

There is no specific clinical presentation of SBEM, fever and chills, abdominal pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, and consciousness disturbance are recognized presentations of SBEM; it is frequently associated with few localizing signs. Case 2 presented with fever, shortness of breath, and sleep disturbance.

The diagnostic criteria of SBEM [18] include positive pleural fluid culture and a polymorphonuclear (PMN) count greater than 250 cells/μl. Patients with negative culture, compatible clinical course, and a pleural fluid PMN count >500 cells/μl were considered as culture-negative SBEM with the exclusion of a parapneumonic effusion. Case 2 was diagnosed with SBEM because he had positive pleural fluid culture and a PMN count greater than 250 cells/μl.

In fact, the diagnosis of SBEM is usually missed, because thoracentesis are not performed routinely in cirrhotic patients with hydrothorax. Furthermore, since SBEM is probably an infection that involves a low concentration of bacteria as is SBP, conventional cultures are not sufficiently sensitive to diagnose the condition. Thus, pleural fluid culture should be performed by inoculating 10 ml pleural fluid into a 70-mL ”Liquoid” Blood Culture (TSB blood culture bottle) at bedside, since it contains an opsonin inhibitor that protects bacteria from further complement or phagocyte-mediated killing. [20]

If SBEM is suspected, empirical IV third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic such as ceftriaxone (1 g every 24 hours for 7-10 days) should be started immediately. Insertion of chest tube to drain the pleural fluid is not recommended by many authors. [20],[23] But, in cases where there is slow clinical recovery or symptomatic SBEM, a repeat thoracentesis is recommended. SBEM was considered by Xiol et al.[20] as an indication for liver transplantation independently of SBP. In case 2, ceftriaxone was commenced empirically, then changed to meropenem as the culture yielded extended-spectrum beta-lactamase E. coli. Furthermore, the fluid was drained by pigtail tube for therapeutic reasons.

E. coli isolation was also described in many cases with colopleural fistulae. In such cases, the fluid culture yielded multiple organisms including E. coli, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas.

In conclusion, E. coli pleural empyema is uncommon; it occurs in parapneumonic empyema, SBEM, or colopleural fistulae empyema. E. coli parapneumonic empyema is infrequent and may cause greater illness severity requiring more aggressive treatment such as appropriate antibiotic and decortication. On the other hand, because SBEM is frequently associated with few localizing signs, a high index of suspicion is essential for the diagnosis. Thus, diagnostic thoracocentesis should be carried out in any patient with hydrothorax who presents with fever, pleuritic pain, encephalopathy, or unexplained deterioration in renal function.

| References |

| 1. | Liang SJ, Chen W, Lin YC, Tu CY, Chen HJ, Tsai YL, et al. Community-Acquired Thoracic Empyema in Young Adults. South Med J 2007;100:1075-80. |

| 2. | El Hiday AH, Khan FY, Almuzrakhshi AM, EI Zeer H, Rasul FA. Colopleural fistula: Case report and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Med 2008;3:108-9. |

| 3. | Ozgür O, Karti SS, Yildiz B, Eren N. Spontaneous bacterial empyema in cirrhosis. Turk J Gastroenterol 2004;15:63-4. |

| 4. | Varkey B. Pleural effusions caused by infection. Postgrad Med 1986;80:213-6, 219, 222-3. |

| 5. | Light RW, Girard WM, Jenkinson SG, George RB. Parapneumonic effusions. Am J Med 1980;69:507-512. |

| 6. | Heffner JE, McDonald J, Barbieri C, Klein J. Management of parapneumonic effusion. An analysis of physician patterns. Arch Surg 1995;130:433-8. |

| 7. | Sahn SA. Management of complicated parapneumonic effusions. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:813-7. |

| 8. | Lin YC, Tu CY, Chen W, Tsai YL, Chen HJ, Hsu WH, et al. An urgent problem of aerobic gram-negative pathogen infection in complicated parapneumonic effusions or empyemas. Intern Med 2007;46:1173-8. |

| 9. | Madhu SV, Gupta U. Clinical and bacteriological profile of hospital acquired pneumonias: A preliminary study. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 1990;32:95-100. |

| 10. | Bansal S, Kashyap S, Pal LS, Goel A. Clinical and bacteriological profile of community acquired pneumonia in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2004;46:17-22. |

| 11. | Marston BJ, Plouffe JF, File TM Jr, Hackman BA, Salstrom SJ, Lipman HB, et al. Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization. Results of a population-based active surveillance study in Ohio. The Community-Based Pneumonia Incidence Study Group. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1709-18. |

| 12. | Marrie TJ, Fine MJ, Obrosky DS, Coley C, Singer DE, Kapoor WN. Community-acquired pneumonia due to Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Infect 1998;4:717-23. |

| 13. | Jonas M, Cunha BA. Bacteremic Escherichia coli pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 1982;142:2157-9. |

| 14. | Tillotson JR, Lerner AM. Characteristics of pneuinonias caused by Esrherichia coli. N Engl J Med 1967;277:115-22. |

| 15. | Ruiz LA, Zalacain R, Gomez A, Camino J, Jaca C, Nunez JM. Escherichia coli: An unknown and infrequent cause of community acquired pneumonia. Scand J Inf Dis 2008;40:424-7. |

| 16. | Garcia N Jr, Mihas AA. Hepatic hydrothorax: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38:52-8. |

| 17. | Haitjema T, de Maat CE. Pleural effusion without ascites in a patient with cirrhosis. Neth J Med 1994;44:207-9. |

| 18. | Xiol X, Castellote J, Baliellas C, Ariza J, Gimenez Roca A, Guardiola J, et al. Spontaneous bacterial empyema in cirrhotic patients: Analysis of eleven cases. Hepatology 1990;11:365-70. |

| 19. | Gur C, Ilan Y, Shibolet O. Hepatic hydrothorax-pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment-review of the literature. Liver Int 2004;24:281-4. |

| 20. | Xiol X, Castellví JM, Guardiola J, Sesé E, Castellote J, Perelló A, et al. Spontaneous bacterial empyema in cirrhotic patients: A prospective study. Hepatology 1996;23:719-23. |

| 21. | Sese E, Xiol X, Castellote J, Rodriguez-Farinas E, Tremosa G. Low complement levels and opsonic activity in hepatic hydrothorax: Its relationship with spontaneous bacterial empyema. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;36:75-7. |

| 22. | Daum-Morelon S, Dupont C, Laurent C, Page B, Rouveix E, Dorra M. Spontaneous Escherichia coli infection of pleural effusion in alcoholic cirrhosis without ascites. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1998;149:389-90. |

| 23. | Runyon BA, Greenblatt M, Ming HC. Hepatic hydrothorax is a relative contraindication to chest tube insertion. Am J Gastroenterol 1986;81:566-7. |

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

| Check |

DOI: 10.4103/1755-6783.85770

| Figures |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2]