Introduction: Various factors, including personality characteristics, are involved in addiction and perpetuation of it. Emotions and the way they are felt and responded are a part of personality that may play a role in showing tendency to drug abuse and perpetuation of this behavior. The present study aimed at investigating emotional difficulties in drug addicts. Methodology: The statistical population of this cross-sectional study included 268 individuals, of which 166 individuals were drug dependence who visited medical centers in Zahedan and Iranshahr. The remaining 120 individuals had no addiction history and were assessed with difficulty in emotion regulation scale. Sample selection was done through convenience sampling technique. Findings: Results suggested that drug-dependent people had significant difference from nondependent individuals in five aspects, namely nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviors, difficulty in impulse control, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity (P < 0.01). These two groups were not different only in one aspect, namely the lack of emotional awareness (P > 0.05). Evaluation of emotional difficulties and gender showed a difference between men and women in nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulty in impulse control, limited access to emotion regulation strategies (P < 0.01), and lack of emotional clarity (P < 0.05). There was no between-groups difference in difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors and the lack of emotional awareness. Conclusion: Although emotional difficulties are not the main factor in the onset and perpetuation of drug abuse, abusers suffer from them. Given the research results and those of other studies, the importance of emotion in etiology, prevention, and treatment of addiction can be highlighted. Keywords: Difficulty in emotion regulation, drug abuse, drug dependence

In addition to the positive and constructive role of emotions in human life, they also have a destructive side. Emotions are problematic when they are expressed improperly, occur in an inappropriate context, are too intense, or last too long.[1] This dual function of emotions indicates the emotion regulation process, in which people regulate and adjust their emotion according to the situation.[2] Emotion regulation process may be automated or controlled, and conscious or subconscious.[3] Researchers have proposed different definitions for emotion regulation. According to Eisenberg and Morris,[4] emotion regulation includes the initiation, maintenance, regulation, and alteration of intensity or duration of internal emotional states, emotion-related motivations, and physical processes that often serve to achieve one’s goals. According to Cole, Martin, and Denis (2004), emotion regulation includes changes that are associated with activated emotions. These alterations include changes that occur within the emotion or other psychological processes (such as memory, attention, or social interactions). Emotion can be looked at from two perspectives: (A) emotion as a regulating factor and (B) emotion as a regulated factor (changes in activated emotions). Emotion regulation, as a psychological variable, has been given special attention from researchers in recent decades (Golman, 1995);[5],[6] Several evidence exists on the relationship of emotion regulation with success and failure in different areas of life,[7],[8] adaptation to life stressors (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, and Reiser, 2000), development and growth of mental disorders,[2],[9] postaccident stress,[10] generalized anxiety,[11] borderline personality disorder,[12] high-risk sexual behaviors,[13],[14] and drug abuse.[15] Gratz and Roemer [16] identified four components of emotion regulation: (1) awareness and understanding of emotions, (2) acceptance of emotions, (3) ability to engage in goal-directed and refrain from impulsive behavior when experiencing negative emotions, and (4) the flexible use of situationally appropriate strategies to modulate emotional responses. Awareness and understanding of emotions, as an important strategy, can be the source and cause of many psychological problems.[15] Difficulty in emotion regulation has been identified as a key element in several psychological models for different disorders including borderline personality disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, eating disorder, and drug and alcohol abuse disorders.[16],[17],[18] Tull et al.[19] also in a study discovered the role of emotional difficulty in high-risk sexual behaviors and multiple sexual partners. The diagnosis of the majority of psychological disorders is based on emotional turbulence, which is fundamentally linked to defective function in emotion regulation. Cole et al.[20] believed that emotion regulation is not synonymous with emotional control and as such, does not necessarily involve immediately diminishing negative affect. It is also a defect in the attenuate of the quantity and intensity of negative feelings.[7],[20],[21] These latter approaches suggest that deficiencies in the capacity to experience (and differentiate) the full range of emotions and respond spontaneously may be just as maladaptive as deficiencies in the ability to attenuate and modulate strong negative emotions. Negative emotions are an integrated part of today’s life; therefore, emotion regulation, as one of the most important physical and psychological health factors, has undoubtedly significant potential in today’s life.[22] Given the importance of emotion regulation, this study was done to provide a better understanding of emotion regulation difficulties in the addicts by comparing them with the nonaddicts.

This is a cross-sectional, descriptive-analytical study. The sample size included 286 individuals, among which 166 individuals were addicted, selected from those visiting addiction rehabilitation clinics in Zahedan and Iranshahr in a 4-month period. In addition, 120 individuals with no history of drug abuse were selected and evaluated, using convenience sampling technique.

Difficulty in emotion regulation scale It is a 36-item scale developed by Gratz and Roemer.[16] The measure yields a total score as well as scores on 6 subscales. These subscales are nonacceptance of emotions, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors, difficulty in impulse control, the lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and the lack of emotional clarity. This scale is responded based on a 5-point Likert scale. Gratz and Roemer [16] investigated the reliability and validity of this scale by applying it to 479 master’s students. This scale showed good internal consistency in the overall score (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93) and all subscales (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.8). The reliability of the test–retest in a 4–8 weeks period was reported to be appropriate (P < 0.01 for subscales and P = 0.88 for the overall score). Khanzadeh et al.[23] examined the reliability and validity of difficulty in emotion regulation scale in an Iranian sample including 363 students of Shiraz University. They reported the Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86–0.88 and retest’s validity coefficient of 0.79–0.91 for these scales after 1 week.

All 286 participants were divided in two groups, namely the addicts (n = 166, 58%) and nonaddicts (n = 120, 42%). The mean age and standard deviation of drug addicts and nonaddicts were 32.65 ± 8.22 and 22 ± 5.79, respectively. Given research findings from investigation into the subscales of difficulty in emotion regulation, it was found that the addicts gained higher scores and means than nonaddicts [Table 1].

According to the findings, there was a significant between-groups difference in nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors, impulse control difficulties, access to emotion regulation strategies, and the lack of emotional clarity (P < 0.01). The only exception with no between-groups difference was the lack of emotional awareness. Results from the comparison of subscales of difficulties in emotion regulation between men and women are presented in [Table 2].

There was a significant gender-difference in nonacceptance of emotional responses, impulse control difficulties, access to emotion regulation strategies, the lack of emotional clarity; whereas, no significant difference was observed in the lack of emotion awareness, and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior.

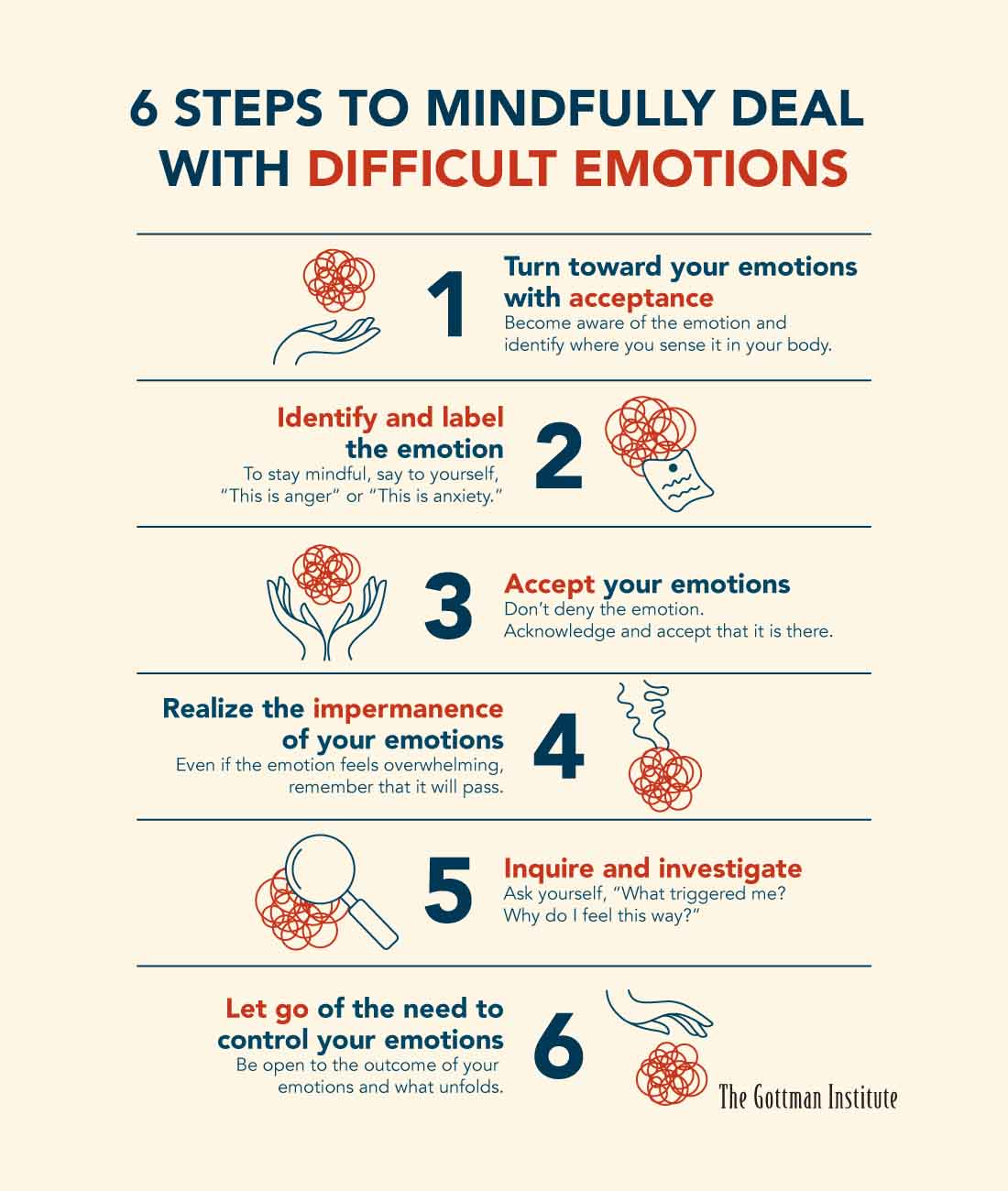

Results from studying emotional defects and difficulties were significantly different in the addicts and nonaddicts. This indicates poor emotion regulation strategies and disability in coping with emotions and emotional management, which are consistent with the findings of Parker et al. (2008), and Goleman’s hypothesis (1995), who reported low emotional quotient in drug abusers. Nonacceptance of emotions in the addicts makes them tended to negative emotional responses while they are facing with emotions. Difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors assess inability to focus on goal-directed behaviors when facing with emotions. According to research results, those with stronger negative emotions have greater difficulties in displaying goal-directed behaviors, which is consistent with the findings of Gratz and Roemer 2004,[16] Tull et al.,[19] 2008, and Orgeta,[24] 2001. Difference in scores of difficulty in impulse control showed that the addicts had difficulties in impulse control and inhibition when they were facing with emotions.[25] Some researchers also indicated that difficulty in impulse control is often associated with relapse in various drugs of abuse.[26] The two groups were not different in the lack of emotional clarity, indicating that they were capable of distinguishing between emotions and motivational messages within emotions. The strategies and approaches of emotion regulation and the lack of emotional clarity were two other investigated variables that show a between-groups difference. The use of maladaptive and inefficient strategies is related to intensity of emotions and poor understanding of them. This behavior is more common among those with more severe emotional impulses.[16] Repression, avoidance and rumination are among inefficient strategies with the maximum impact on mental disorders.[27] The lack of clarity and poor understanding of emotions increase the sense of sadness in the person. This results in the use of maladaptive coping strategies by that person (Steven et al., 1996). Since behavior and thought are functions of emotions, any disorder and defect in emotional system can lay the ground for several disorders or be affected by them.[28] According to Cole,[20] emotion regulation means compliance and flexibility in the use of emotion regulation strategies. Emotional adaptation includes changes in the intensity and duration of a feeling instead of emotional alteration and dissociation.[29],[30] Emotional adaptation deals with emotional experiences instead of removing and suppressing emotions. In this model, the perception of motivation decreases anxiety and increases one’s control over his/her emotions and behaviors. In addition, it leads to the control of impulses and inappropriate behaviors, and the achievement of desired goals during emotional experience (Hinshaw, 2000). In the explanation of results, two factors can be indicated: (1) drug abuse causes emotional defect, and (2) emotional defect and poor emotion management increase the probability of drug abuse. Management capability and appropriate emotion regulation strategy can contribute to healthy coping strategies (leaving the location and power of saying no) and/or unhealthy strategies (coming under pressure, consumption) when there is a risk of drug abuse. Individuals capable of positive emotion regulation are also more capable of predicting others’ demands, understanding others’ unwanted pressure, and controlling their emotions; as a result, they have higher resistance to drug abuse.[31] Therefore, given limited access to emotion regulation strategies and difficulties engaging goal-directed behavior, emotion-based psychological interventions including dialectical behavior therapy [10] emotion-oriented therapy,[21] acceptance-based behavior therapy and mindfulness,[32] emotion regulation therapy,[33] which target emotion attenuation and defect, need extra attention.[34] Financial support and sponsorship Nil. Conflicts of interest There are no conflicts of interest.

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

[Table 1], [Table 2] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||