| Abstract |

This paper introduces an alternative comprehensive approach to reduce sexual exploitation and child prostitution. The paper focuses on female devadasi temple prostitutes (Child sex workers but popularly understood as temple prostitutes in the name of dedication to deity) children in South India and the provision of support to integrate devadasi girls into the community and improve their psychosocial situation. The paper is designed broadly, taking cultural practices into consideration and also with a community participatory approach to achieve the goal. The broad objective of the paper is to promote alternative policy approaches, such as: 1. Community participation to integrate current devadasi girls into regular community life, 2. Community participation to avoid future initiation of young girls into the devadasi system, 3. Meeting the psychosocial needs through health, counseling and economical needs of devadasi girls in the community, 4. Assistance to devadasi girls as an alternative to devadasi service in the community. The policy advocacy includes participation by key community members and women’s local Self-Help Groups (SHG’s) networking to support existing devadasi girls to overcome stigma, social discrimination through cleansing rituals, and organizing vocational training skills to enhance their economic status. Other policy issues are integration of primary healthcare services to these girls and extending counseling services on sexual health and behavioral practices and also to introduce a micro credit system to existing devadasi girls. The paper draws its conceptual framework from psychosocial working group to provide comprehensive strategies to address community complexities. A community participatory approach has been proposed to adopt, in order to build a sustainable strategy to provide the psychosocial needs of the girls initiated into devadasi services, especially in South Indian states where it is prevalent.

Keywords: Devadasi system (temple prostitute), policy practices in sexual subject, sexual exploitation

| How to cite this article: Sathyanarayana T N, Babu GR. Targeted sexual exploitation of children and women in India: Policy perspectives on Devadasi system. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2012;5:157-62 |

| How to cite this URL: Sathyanarayana T N, Babu GR. Targeted sexual exploitation of children and women in India: Policy perspectives on Devadasi system. Ann Trop Med Public Health [serial online] 2012 [cited 2020 Nov 23];5:157-62. Available from: https://www.atmph.org/text.asp?2012/5/3/157/98603 |

| Introduction |

The term devadasi is derived from the Sanskrit language: ‘deva’ means God and ‘dasi’ means servant. [1] Devadasis are female children dedicated to goddess through marriage to a deity. After the marriage ceremony they become deities’ wives and continue to perform the traditionally decided duties such as dancing, sexual services to temple patrons and the priests. [2] As per O’Neil, [3] the tradition of devadasi is predominantly seen in South India, and they are popularly known as ‘temple dancers’; the young girls are dedicated to a village temple god through marriage. They may function as servants at village temples once they attain the age of maturity (Maturity is generally understood in the region as post-pubertal period). Traditionally, they are expected to perform dancing combined with other local artistic functions, as well as sexual services to patrons and priests of the temple. [3]

History of Devadasi system

Observing recordings of the term devadasi in local language, the beginning of the devadasi system traces back to 1113 AD at Alanahalli village of Karnataka. [5] The devadasi system continues to be practiced in the majority of villages in certain provinces of India. In the late 19 th century, the colonial government system imposed several pieces of repressive legislation for wider social reforms. During this period, the position of devadasis in the society had changed marginally. However, the devadasi system continues to exist because of the deep socially embedded ritual of marriage to God. [6] With the advent of the Karnataka legislation act 1982 ‘Devadasis prohibition of dedication’ to ban this system, the devadasis moderately lost their position of socio-religious status in the society. Nevertheless, significant features of the system persist. [7] According to United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), [8] the devadasi prostitution system still continues with religious sanctity in India. The devadasi system (popularly known as temple prostitution) allows sexual exploitation of young girls by temple patrons and priests in the name of dedicating such young girls to God. The religious devadasi is a form of prostitution, which continues in South India. [8]

Problem analysis

Currently, the practice of induction and sustenance of devadasi is largely consistent with the earlier traditional system. The initiation of a young girl’s dedication to God begins at around 6-9 years of age. [4] Tarachad [3] states that, an initiation ceremony into devadasi typically begins around the age of 5-10 years. However, they become full-fledged devadasis (practice of devadasi service) only after attaining puberty to avoid unwanted pregnancies or because of their family’s circumstances. [3]

In majority of the villages, the devadasis are not allowed to participate in auspicious ceremonies. [9] The devadasi system exploits a subset of women systematically in the form of discrimination, social exclusion and stigma against prostitutes. Also, devadasis have been forced not to engage in any alternate profession [4] in some parts of South India. The majority of devadasis in the southern states of India continue to live in their native villages, with no improvement in their low socioeconomic or low caste (untouchables) status. Devadasis usually live separately within larger village communities [7] due to several layers of societal problems coupled with the requirements of the profession they practice.

The reasons for the dedication of the girl child to temple services vary from place to place [Table 1]. A common reason is that one girl per devadasi family is supposed to be initiated into the Devadasi system. Other reasons are absence of a male child in the family, to please deities during grave sickness or drought or as a boon to a deity for a particular prayer. [3]

| Table 1: Reasons for becoming devadasi (temple prostitute)

Click here to view |

Despite the legal implications of the most recent initiative into devadasi system, ceremonies take place in concealed settings, typically conducted by priests extracting considerable amounts of money for the ceremony service. [3]

Historically, devadasi system was practiced due to a combination of cultural practices, socioeconomic status, local political views, religious belief, and ritualized role in the society. However, currently, the devadasis are forced to take their current profession to meet the daily economic requirements of personal and family members. For example, older devadasi women or mother of girl, typically announce a girl’s sexual maturity (initiation into devadasi begins in age group of 6-13 years but practice of davadasi usually starts after puberty (sexual maturity). According to a study review by Blachard et al.,[9] 40.3% of girls have engaged in devadasi sexual services before 15 years of their chronological age [9] ) to attract potential customers for the ‘first ceremony’. A devadasi’s mother can charge higher service fee (Rs 1,500-15,000 or £ 30-300) or can demand gold gifts and other forms of wealth, due to the importance given to first ceremony. [4] Blachard et al.[9] state that 75.6% of devadasis confirm that more than half of their income is generated from sex work. This shows that devadasi system continued to exist in the current scenario primarily because of economic threat and social exclusion. Further, inability to join other profession might have possibly forced to these women to continue in the devadasi system.

Policy concern

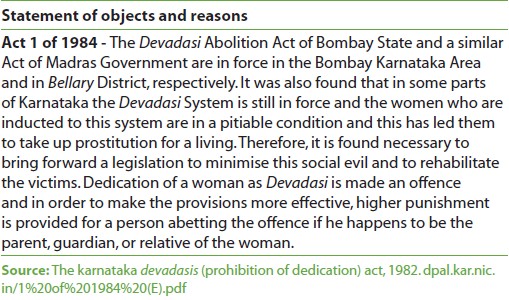

Despite the government’s commitment and legislation [Table 2], the complex challenges to integrate devadasi girl children into normal community life continue to exist.

|

Table 2: Abstract of The Karnataka State Devadasis (Prohibition of Dedication) Act, 1982 India |

The legislative actions in terms of legal acts of erstwhile Bombay state, Act of Madras and Karnataka State’s Prohibition of dedication Act of 1982 had limited success in eliminating the practice of the devadasi system. Hence, pragmatic efforts are essential to integrate devadasi initiated girl children into community life to improve physical, emotional, and psychosocial health through sustainable comprehensive approach.

Magnitude of the problem

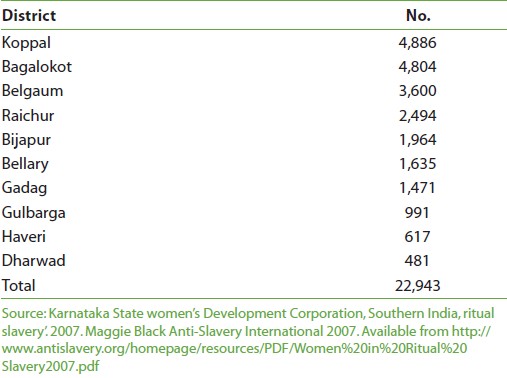

The number of devadasi dedications and the total number of devadasi girls in South India is difficult to obtain because most of the traditional devadasi sex work is now home-based in rural villages and these girls continue to serve where they reside. Other reasons for estimations of the exact numbers are due to methodological inconsistencies of earlier estimations, fear of legal implications of admitting the status and stigma of discrimination when disclosing this to outsiders. However, recent estimates have identified that approximately 1,000-10,000 young girls are introduced into the devadasi system annually in India. [10],[11] The latest available official figure for key districts in Karnataka state alone (India) is about 23,000 as shown in [Table 3]. [12],[13]

|

Table 3: Number of devadasis in Karnataka state of India (district wise) |

Effects of devadasi system on girl children

Psychosocial: The imaginary wives of the God are excluded socially, stigmatized morally, and have additional problem of facing widowhood. All these factors may lead devadasis to feel depressed and may manifest with abnormal changes in their behavioral pattern. Over a period of time, they are likely to suffer from psychosomatic disorders and may live unnoticed in the community. [14]

Physical : Young girls’ reproductive function before growth results in stunted skeletal growth, high risk of obstructed labor, and can lead to vesico-urethral, vesico-vaginal, or vesico-anal fistula and infection. [15] The health risks are further multiplied by poor nutritional and health support from the family and community. The growth spurt at the adolescent age is further reduced by inadequate nutrition and psychological stress may lead to psychosomatic disorders; moreover, these girls are likely to face three times higher complications as compared to older women. [16] In short, young girls initiated into the devadasi system are potentially at a high risk of becoming victims of health and psychological stress factors. According to a recent survey, in Karnataka state of India alone, 26% of female sex workers are entering into sex work through the devadasi system. Most of them are now struggling to develop healthy sexual practices, grappling with the stigma of their profession, HIV, and other Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs). [4]

Conceptual framework

Psychosocial working group framework: As mentioned in the situation analysis, the integration of devadasis into the community is a complex social and cultural issue. Therefore, community participation is essential as the devadasi system is deeply embedded in the culture of the community. Simultaneous efforts will have to be implemented to build confidence, self-esteem, and economic status among devadasi initiated girls. We propose adopting a psychosocial working group framework [17] to provide comprehensive tools to design the program [Figure 1].

| Figure 1: A psychosocial working group framework

Click here to view |

The psychosocial working group defines psychosocial well-being in three main areas of Human capacity, Social ecology, and Culture and values. Most of the existing problems toward eliminating the devadasi system can effectively be tackled by a balanced approach of each core area of the framework through community participation. We infer that beyond this model, steps need to be taken to address economic and physical barriers (access to primary healthcare services).

Using the framework, we propose to improve the resilience of existing devadasi adolescent girls and encourage community participation to prevent future occurrences of devadasi ceremonies. Implementation of a comprehensive package is essential to enable the devadasi girls and women to cope up with the psychosocial issues, physical health issues, and economic issues in their lives. It is vital that a smooth transition mechanism be implemented to switch these deprived women from the traditional system of dedicating to deities into existing social system through community participation.

| Discussion and Conclusions |

Devadasi is an issue of child prostitution. This form of “slave trade” constitutes a contentious debate in the development sector, as exploitation of young girls is done in the name of ritual practices. This system hampers individual and social development and has evolved into significant issue in some rural areas of southern India. These young sex workers in ‘southern rural India’ are oppressed through several layers of victimization, impoverishment, and retrograde cultural traditions. No construct available to us can capture the complexity of the experiences or the mental/physical health problems faced by devadasi women. Based on policy analysis with girls and young women who are part of the devadasi (slave/servant of the God) system of sex work in India, this paper explains the social, economical, and cultural constructs embedded in certain regions of rural South India, thereby proposing a new policy perspective. We propose that acceptance and implementation of psychosocial working group framework may create social environment by involving devadasi girls and community on the same platform, and devadasi girls might get comprehensive support as they grow up. After acceptance of the policy framework, the biggest challenge will be how to integrate devadasi girls with local communities. Therefore, community participation is essential as the devadasi system is deeply embedded in the culture of the community; simultaneously, efforts are needed to build confidence, self-esteem, and economic status among devadasi initiated girls. Therefore, we propose to focus on psychosocial, health, educational, and economic issues. The systems’ approach can further develop and meet measurable indicators to ensure the acceptability of the initiative.

| Recommendations |

Target and segment the groups: It is better to concentrate efforts toward elimination of Devadasi system in a few highly prevalent districts in southern states of India for the reasons of geographical proximity and operational feasibility. Segmentation of individual and collective socio-cultural and economic issues might target devadasi system more efficiently. The use of psychosocial working group framework for implementation of the program can be done by the local government through local community participation.

Integration of devadasi girls into community life: This can be done by networking with local Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and collaborating with community-based organizations. This can be done by facilitating participation of families and key community members to help devadasis integrate into community life. This can begin as dialogue with temple priests and other key religious heads and convincing them to organize social purification rituals to provide social sanctity and the community may be encouraged to participate in such ceremonies. The involvement of the community is likely to reduce the social stigma and discrimination, which indirectly support the psychosocial stress of devadasi girls.

Improve the economic status of devadasi girls to strengthen resilience capacity: This can be done by collaborating with an ongoing job-oriented training program at regular intervals to improve the skills of unemployed youth; these programs should be run by district training centers through government social welfare schemes. Efforts may be made to impart specific job-oriented training programs to identified devadasi girls through formal communication to the social welfare department. The trainings may be customized in small groups to train in specific areas such as tailoring, knitting, weaving, candle making, envelope making, vegetable vending, and small provision shop management. Depending on each devadasi girl’s interest and skills, micro credit loan system may be introduced for economic self-sustainability. This effort may attempt to increase confidence, self-esteem, and independence of such girls. The group interaction may provide enough room to share views, opinions, and emotional and psychological support.

Provide primary healthcare, health education, and counseling services: A separate formal meeting may be organized with primary healthcare staff to provide specific treatment and nursing service requirements to devadasi initiated girls. Primary healthcare staff may be trained to provide counseling services to those in need. Female midwives (field health workers) may have access to and build connectivity with davadasi families. Since female midwives are culturally accepted, the paper proposes to utilize the services of midwives effectively to gain access and initiate health services with devadasi families. Initially, the health services may be provided with good quality medicines, contraceptives, counseling services through primary healthcare center, and midwives field services. This may build trust and confidence in the community and improve sexual health and psychosocial support through counseling services.

Assistance to devadasi culture challenged girls: Some of the Devadasi initiated girls may not be willing to change their lifestyle. Such devadasis should not be left out of the program. Efforts may be made for such a section or group of girls to participate in job-oriented training, micro credit loan system, and the primary healthcare service provision, and also by encouraging them to participate in one-to-one and group meetings. A committee of key community members may understand, negotiate, and help such girls to overcome the devadasi system. Religious heads may be motivated to go for more ritual cleaning ceremonies to change the attitude of such unwilling girls.

Change of community attitude and practices toward the devadasi system and the building a sustainable devadasi-free community: A community committee may be constituted, including key stakeholders such as village heads, representatives from women’s SHG’s, a few devadasi family representatives, the welfare department, primary healthcare workers, religious heads, and other community-based organizations. The community committee members may receive training based on ‘children’s rights’, ‘girl child health and psychosocial’ issues, and scope of ‘community participation’ to strengthen the program.

Peers/mentors: The paper recognizes that the role of peer mentors is crucial in influencing sexual victims through exemplary testimonies that reduce stigmatization. Therefore, it is recommended that peer mentors need to be nurtured, who can strive to establish good working relationships with peer members on a daily basis through motivational strategies such as recognition and rewards. [17] The government has made commitments to reduce poverty through good governance and political stability.

Monitoring and evaluation: These activities can be designed to protect health and psychosocial development and to assess progress. These can include assessing psychosocial factors, provision of health services, change in community behaviors, and imparting vocational training skills as priority areas. The objectives and connected activities need to be designed in line with situation analysis, by adopting both qualitative and quantitative indicators to guide progress of the welfare initiative toward abatement of the devadasi system.

| Acknowledgement |

The paper has been reviewed before submission by Dr Rahul Shidhaye, MD (Psychiatry). The authors express gratitude towards his valuable suggestions and support while preparing this manuscript.

| References |

| 1. | Goswami KP. Devadasi. Dancing damsel. New Delhi: APH Publishing Corporation; 2000. |

| 2. | Tarachand KC. Devadasi custom, rural social structure and flesh markets. New Delhi: Reliance Public House; 1992. |

| 3. | O’Neil J, Orchard T, Swarankar RC, Blanchard JF, Gurav K, Moses S. Dhandha, dharma and disease: traditional sex work and HIV/AIDS in rural India. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:851-60. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURLand_udi=B6VBF-4BFXP752and_user=1103673and_rdoc=1and_fmt=and_orig=searchand_sort=dandview=c and_acct=C000051645and_version=1and_urlVersion=0and_userid=1103673andmd5=6f3 8b4116e2e31607427ba71fb6d9550. [accessed on 2008 Apr 29]. |

| 4. | Shankar J. Devadasi cult: A sociological analysis. New Delhi: Ashish Publishing House; 1990. |

| 5. | Levine P. Venereal disease, prostitution, and the politics of empire: The case of British India. J Hist Sex 1994;4:579-602. |

| 6. | Orchard TR. Girl, woman, lover, and mother: Towards a new understanding of child prostitution among young Devadasis in rural Karnataka, India. J Soc Sci Med 2007;64:2379-90. Available from: http://www.springerlink.com/content/u38121502n51gt8q/. [Last accessed on 2008 Apr 3]. |

| 7. | UNICEF. Commercial sexual exploitation and sexual abuse of children in South Asia. 2nd World Congress against Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children. Yokohama, Japan: 17-20 December 2001. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/rosa/South_Asia_Strategy_Yokohama.pdf. [Last accessed on 2008 Apr 6]. |

| 8. | Evans K. Contemporary Devadasis: Empowered auspicious women or exploited prostitutes? Bulletin John Rylands Library University Library of Manchester 1998;80:23-38. Available from: http://sumaris.cbuc.es/cgis/sumari.cgi?issn=0301102Xandidsumari=A1998N000003V000080. [Last accessed on 2008 Apr 6]. |

| 9. | Blachard JF, O’Neil J, Ramesh BM, Bhattacharjee P, Orchard T, Moses S. Understanding the social and cultural contexts of female sex workers in Karnataka, India: Implications for prevention of HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2005:191(Suppl-1):S139-46. Available from: http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/425273?cookieSet=1. [Last accessed on 2008 Apr 15]. |

| 10. | Giri VM. Kanya Exploitation of little angels. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House; 1999. |

| 11. | Chakraborthy K. Women as Devadasis Origin and Growth of the Devadasi Profession. New Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications Pvt Ltd; 2000. |

| 12. | NWC 2002. As mentioned in Chawla A. Devadasis-sinners or sinned against. An attempt to look at the myth and reality of history and present status of Devadasis 2002. Available from: http://www.samarthbharat.com/files/devadasihistory.pdf. [Last accessed on 2008 Apr 10]. |

| 13. | KSWDC. Karnataka State women’s Development Corporation figures on devadasi as mentioned in ‘Women Devadasi in, Jogini and Mathamma in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, Southern India, ritual slavery’, 2007. Maggie Black. Anti-Slavery International 2007. Available from: http://www.antislavery.org/homepage/resources/PDF/Women%20in%20Ritual%20Slavery2007.pdf. [accessed on 2008 Apr 9]. |

| 14. | Kersenboom S. Nityasumangali: Devadasi tradition in South India. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass; 1987. |

| 15. | Giridhara R. Babu Re: “Problems Related to Menstruation amongst Adolescent Girls” by P Sharma et al. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 77, 2008, 218-219. doi:10.1007/s12098-009-0270-3 |

| 16. | Harrison K. Rural studies in Family planning. Br J Obstet Gynecol 1985. as cited in Cook RJ. International human rights and women’s reproductive health. Stud Fam Plann 1993;24:73-86. |

| 17. | PWG. Psychosocial working group framework 2003. Available from: http://www.forcedmigration.org/psychosocial/papers/Conceptual%20Framework.pdf. [Last accessed on 2008 Apr 7]. |

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

| Check |

DOI: 10.4103/1755-6783.98603

| Figures |

[Figure 1]

| Tables |