Background: Basic infection control measures in any healthcare setup can reduce the rates of healthcare-associated infections. A study to assess the knowledge and practice of 400 healthcare personnel regarding hospital infection control practices was performed. Materials and Methods: A structured questionnaire was distributed to the study group and collected the same day. Knowledge and practices of 329 nurses and 71 doctors regarding hand hygiene, SPs, hospital environmental cleaning and needle stick injury were collected and analyzed. Results: The study group had suboptimal knowledge regarding the SPs (55.3%) and risks associated with NSI (31.8%). The implementation of SPs was biased towards the HIV positive status of the patient. Only 57% of the doctors and nurses followed the maximal barrier precautions before a CVC insertion. Discussion: The lack of knowledge and practices regarding basic infection control protocols should be improved by way of educational intervention, in the form of formal training of the doctors and nurses and reinforcement of the same. Keywords: Doctors, hospital infection, nurses, standard precautions

Healthcare-associated infections (HCAI) are a major set back to any organization. The prevalence of HCAI varies widely across the globe. Worldwide it is estimated that almost 10% of the hospitalized patients acquire at least one HCAI. [1],[2] The prevalence of HCAI in developing countries can become as high as 30-50%. [3],[4] Many of these pathogens implicated in HCAI are often multi-drug resistant and are able to survive in the environment for a long period of time. [5,6] The most important mechanism of spread of these HCAI is via the contaminated hands of the healthcare givers that is doctors, nurses, other staff or relatives/friends of the patients. [5],[6] Contaminated environmental surfaces are another important reservoir for spread of these infections. However, they are often under-recognized. Infection can also spread to patients by drugs, intravenous solutions or by foodstuffs. [5],[6] These HCAI are associated with increased morbidity, mortality and healthcare expenditures. Due to these clinical, ethical and financial factors, healthcare providers are increasingly paying more attention to surveillance and prevention of HCAI. There are several evidence-based methods that have reduced the rate of HCAI. Hand hygiene is by far the most effective method in reducing the prevalence of HCAI. The healthcare personnels are also at increased risk of infection from blood-borne pathogens (BBP) like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV). Percutaneous injuries caused by needles and sharps are responsible for infection due to BBP. Exposure to infectious material can be minimized if they adhere to standard precautions (SPs). [7] Besides the documented role of hand washing and SPs, other non-pharmacological interventions such as cleaner hospital environment have been shown to significantly reduce the rate of HCAI. [8] But these are often overlooked in practice. The present study was undertaken to assess the awareness of these HCP regarding basic infection control practices such as hand hygiene, SPs, needle stick injury (NSI), post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and environmental cleaning protocols of the hospital.

The study was conducted in a 700-bedded tertiary care super specialty hospital from September 2009 to December 2009. The study done was a cross-sectional survey of the HCP including doctors and nurses involved with direct patient care. The 25-item survey questionnaire was distributed to the HCP during regularly scheduled infection control rounds and educational meets. The respondents were required to fill the survey and return it on the same day to avoid any response bias because of any collaboration amongst them. Only the questionnaires that were complete were included for the final analysis and any questionnaire which was incomplete was excluded from the final analysis. The survey collected demographic details including age, sex, professional qualification and years of experience. The content of the questionnaire was based on the infection control protocols followed in our hospital with further relevant questions related to the everyday practice of the medical staff. The final questionnaire comprised of 25 main questions related to knowledge and practice regarding hand hygiene (7 questions), SPs and maximal barrier precautions (8 questions), NSI and post-exposure prophylaxis (5 questions) and hospital environment cleaning including blood spillage and biomedical waste management (5 questions). Statistical analysis: The responses were recorded in the computer using statistical software SPSS and analyzed. A comparative analysis was performed between two groups (doctors vs. nurses) using Chi-square and Fisher’s test for significance. A p value of ≤0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Four hundred questionnaires were included for the final analysis. The study group comprised of 71 resident doctors and 329 nurses. Based on the working strength of our hospital the study group represented 25.3% of doctors and 31.5% of the nurses. The demographic details of the study group are shown in [Table 1].

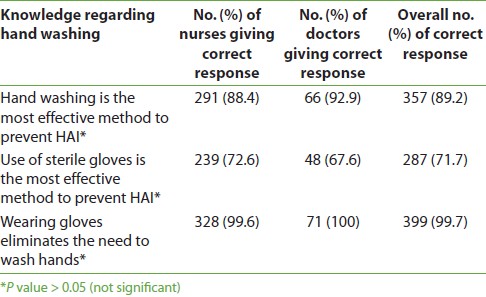

The mean experience of HCP in our set up was 8.6 years. The respondents were asked few questions to assess their knowledge regarding hand washing [Table 2]. The mean knowledge regarding hand hygiene was 86.8% in the study group. There was no difference in the response of the doctors and nurses. The respondents were asked to identify how important they thought certain aspects of SPs were [Table 3]. The knowledge regarding the components of SP was uniformly poor being only 55.3% amongst both the doctors and nurses. The doctors (71.3%) had significantly more knowledge regarding the SP as compared to the nurses (52%). Only 28.5% of the study group identified avoiding injury with sharps as one of the important components of SP.

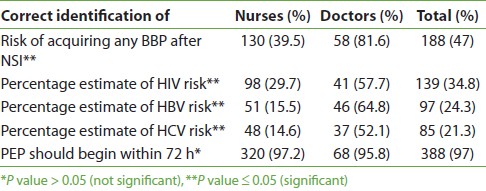

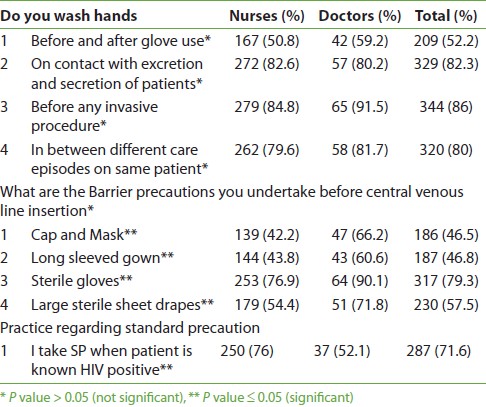

The knowledge regarding the transmission of blood-borne pathogens and their approximate risk was suboptimal (31.85%) with significantly less awareness being of nurses (24.8%) as compared to the doctors (64%) [Table 4]. The study group was aware that PEP should begin as early as possible after an NSI. Infection control practices of the study group are as shown in [Table 5]. The practice as regards the maximal sterile barrier precautions was a dismal 57.2%. Less than half of the study group used cap, mask and gown as part of maximal barrier precautions. Nurses used these maximal barrier precautions significantly less in comparison to doctors. The HIV-positive status of the patient was an important factor in the implementation of the SPs.

The nurses had significantly more knowledge than the doctors regarding the correct protocol for environmental cleaning as per our hospital policies [Table 6]. There was considerable scope of improvement as on an average only 74.9% of the study group was aware of the correct protocols.

Approximately 82.7% of the sisters were aware of the correct cleaning protocol while only 61.4% of the doctors were aware regarding it. The difference between both the groups was statistically significant.

The obvious limitation of our study was the selection of only a representative sample and the lack of pre- and post-educational survey in the same sample. The study was made on the assumption that study group selected had been exposed to the educational material that is being circulated in our hospital either in the form of lectures, educational meets or pamphlets and thus were aware of the infection control measures to be practiced by them. The compliance for the infection control practice was measured based on their response. A more effective way of measuring compliance would have been to monitor them. However, this also could result in erroneously higher compliance as per the Hawthorne effect. Infection control practices are of paramount importance in any healthcare setup for prevention of HCAI. Hand hygiene is the first initial step towards successful infection control in any healthcare setup. [9] We found that in our set up knowledge regarding hand hygiene was 86.8% but the actual compliance was less (75.1%) as compared to their knowledge. In our hospital, we enforce the importance of hand hygiene for infection control at every possible opportunity for interaction with the HCP. This could be the reason for improved knowledge. Other authors have observed the low compliance of HCP towards hand hygiene also. In a meta-analysis the hand washing compliance was 52% (range 27-86%). [10] Many authors have identified reasons for this non-compliance which included, lack of time, lack of means, patients not at risk or forgetfulness. In our set up probably similar reasons could have led to the low hand hygiene compliance. Our study demonstrated considerable scope for improvement regarding the knowledge and implementation of SPs. Only 28.5% of the respondents could identify avoiding injury with sharps as a component of SP and only 52% could identify barrier precautions as a component of SP. The compliance to implementation of SP was biased towards the HIV positive status of the patient. The findings in our study are consistent with previous reports of suboptimal compliance with SP and attitude of HCP towards HIV positivity. [10],[11],[12] The attitude and practice of being extra careful when a patient is a known HIV positive need to be changed as this makes the HCP less vigilant in handling other patients. CDC recommends that every patient should be treated as potentially infectious and all SP must be taken since many of these patients might be having a hidden infection with these BBP. Therefore, it is imperative that SP should be observed as a rule and not as an exception. On enquiring about the maximal barrier precautions they take before the insertion of CVC, both the nurses and doctors response was that of a suboptimal compliance (57.5%). On comparison, nurses (54.3%) were lagging far behind the doctors (75.2%). Though doctors perform CVC insertion in our hospital we feel nurses as assistants should also observe full barrier precautions. This finding has important implications as catheter-related blood stream infection (CRBSI) can largely be prevented by use of simple means such as maximal barrier precautions by both the operator and the assistants. [13] Transmission of at least 20 different pathogens by injury to sharps has been reported in the literature. [14] Hence, the HCP should be aware regarding the risks associated with these BBP. Another shortcoming that came to light was the significant difference between the awareness levels of doctors and nurses regarding the risk of acquisition of these BBP. Only 39.5% of the nurses were aware about the risk of transmission of these BBP following an NSI as compared to 81.6 of doctors. This lack of knowledge regarding BBP has been observed by other authors also. In one of the study, only 25% of the respondents were aware regarding the risk of acquiring BBP. [11] In another study the difference between nurses and doctors knowledge regarding BBP was significant. [15] The study group was not aware about the percentage estimate of risk of these BBP and most of them felt HIV was most contagious. The difference was again significant and doctors were more knowledgeable. This could be because doctors during their course study are taught about the risk of infection due to individual viruses. Hospital environment acts as a reservoir for many of these potential pathogens and there is documented evidence that environmental cleaning reduces the rates of HCAI. [6],[8] Hospital environment as a source of transmission is often overlooked in practice. Correct environmental cleaning protocol as per our hospital infection control policies were being followed by over 82% of sisters. Doctors were significantly less aware (61.4%) regarding the same. This could be because the infection control team at our hospital carries out target-based education. The cleaning of hospital environment is the responsibility of the house keeping staff under the supervision of the nurses. Though doctors are not directly involved in the cleaning protocols we feel that they should at least be aware of these protocols so that they can monitor increasing HCAI rates. Thus, the present study reiterates the finding that educational intervention does affect knowledge and implementation of infection control practices at any healthcare setup. Though no direct evidence is available to support this finding, we have many indirect evidences to prove so. The protection of HCP in many developing countries is often ignored by the authorities and more importantly by the HCP themselves. Our study points out that there is always a scope for improvement in the infection control practices being followed. It would be beneficial for all HCP to receive formal training regarding the same. Educational training programmes or still better would be a multidisciplinary intervention in the aura of a quality control circle to help these HCP realize the importance of basic infection control practices such as hand hygiene, SPs, risk of NSI, post-exposure prophylaxis and cleaning of hospital environment. It is obvious that routine use of these infection control practices by HCP would help reduce the rate of HCAI in any healthcare setup.

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

[Table 1], [Table 2], [Table 3], [Table 4], [Table 5], [Table 6] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||