| Abstract |

A 55-year-old diabetic female presented with persistent headache, bilateral nasal blockage, common cold and nasal discharge since 10 days. The patient also complained of bilateral nasal bleeding, anosmia and ptosis of the eye since the last five days. Clinical diagnosis of rhino-orbito-cerebral was confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan of paranasal sinuses and brain. The diagnosis of fungal infection due to Rhizopus species was confirmed by Potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination, Hematoxylin and Eosin staining and Gomori’s Methenamine Silver Nitrate staining on mucosal biopsy, followed by culture on Sabouraud’s Dextrose agar. Surgical debridement was done and intravenous Amphotericin B was administered to the patient, who responded well to the treatment.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, rhino-orbito-cerebral infection, Rhizopus species

| How to cite this article: Baradkar V P, Kumar S, Mathur M. Rhino-orbito-cerebral infection due to Rhizopus in a diabetic patient. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2010;3:23-5 |

| How to cite this URL: Baradkar V P, Kumar S, Mathur M. Rhino-orbito-cerebral infection due to Rhizopus in a diabetic patient. Ann Trop Med Public Health [serial online] 2010 [cited 2020 Aug 14];3:23-5. Available from: https://www.atmph.org/text.asp?2010/3/1/23/76180 |

| Introduction |

Mucormycosis is an aggressive life-threatening, opportunistic infection occurring in patients with severe diabetes and immunosupressed conditions, caused by one of the ubiquitous, saprophytic fungi of the order Mucorales.[1] The fungi are usually harmless commensals, but in extraordinary circumstances they cause invasive disease. The most common form of disease presentation is rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis, although primary infections of the skin, lungs and gastrointestinal tract have also been reported. [2] The most common agent causing human disease is the Rhizopus species followed by Rhizomucor. Other zygomycotic fungi reported from cases of rhino-cerebral mucormycosis are Absidia, Mucor, Mortirella, Cunninghamella, Saksenaea and Apophysis elegans.[3] The diagnosis should be made on histological grounds as positive cultures may merely indicate the presence of this ubiquitous saprophyte and not necessarily invasion. Culture is required to identify the species. [3] Here we report a case of rhino-orbito-cerebral infection due to Rhizopus species in a 55-year-old diabetic female, who was successfully treated by surgical debridement and Amphotericin B.

| Case Report |

A 55-year-old female presented with persistent headache, bilateral nasal blockage, nasal discharge since 10 days. The patient had a history of bilateral nasal bleeding on and off since five to six days and drooping of upper eyelid for the same duration. The patient was a known case of diabetes mellitus, detected five years back. There was no history of hypertension. The patient had a past history of tuberculosis seven years back, for which she had received antitubercular drugs for six months.

On examination the patient was afebrile, with a pulse of 88/min, blood pressure of 140/80 mm Hg. Findings of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems were within normal limits. Abdominal examination revealed no obvious enlargement of the spleen or liver.

Examination of the nose showed presence of bilateral nasal crusts, with bilateral mucopurulent discharge and bilateral frontal sinus tenderness was present.

Ophthalmic examination revealed ptosis on the left side, restriction of eye movements in the upper quadrant along with absence of corneal reflex. The examination of the right eye was within normal limits. Central nervous system examination showed that the higher neurological functions were within normal limits except for features of third cranial nerve palsy.

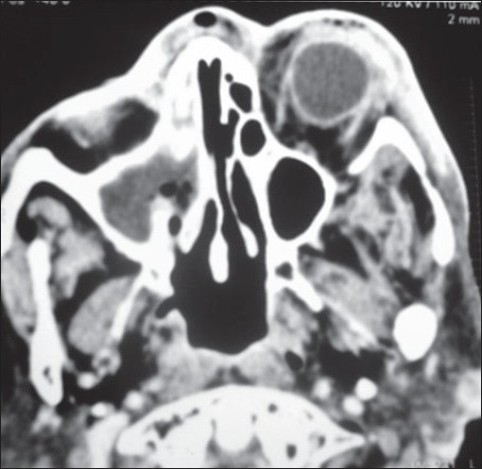

The routine blood investigations revealed hemoglobin of 11 g/dl, total count of 14900/ mm 3 , differential leukocyte count of polymorphs 75%, lymphocytes 24% and eosinophils 1%, the platelets were adequate on peripheral smear. Her fasting and postprandial levels of blood sugar were 100 mg/dl and 220 mg/dl respectively. Her liver and kidney function tests were within normal limits. CT scan [Figure 1] showed proptosis in the left eye, extensive inflammatory changes in the preseptal (intra and extra-conal spaces) compartments of the left orbit in the form of soft tissue swelling and edema with small pockets of inflammatory collection/ phlegmon with involvement of extra-ocular muscles (superior, medial and lateral rectus) which were mildly swollen. Some portions of the optic nerve also appeared mildly swollen. Gross muco-inflammatory soft tissue was observed in the right maxillary sinus, anterior and mid-ethmoidal air cells, and frontal sinus extending into the right nasal cavity. Some muco-inflammatory soft tissue was also seen in the left ethmoidal air cells and left frontal sinus. Right osteo-meatal complex was compromised. The visualized cavernous sinus showed normal enhancement.

|

Figure 1 :CT scan showing proptosis in the left eye, extensive infl ammatory changes in the preseptal (intra and extra-conal spaces) compartments of the left orbit in the form of soft tissue swelling and edema with small pockets of infl ammatory collection/ phlegmon with involvement of extra-ocular muscles

Click here to view |

The treating physician sent the biopsy samples for histopathology, which showed aseptate hyphae in KOH preparation and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H and E) staining. Repeat biopsy showed similar findings on KOH mount and H and E staining [Figure 2] and Gomori’s Methenamine staining (GMS) [Figure 3], showing features suggestive of mucormycosis. Based on these findings, partial debridement of the soft tissue in the sinuses was done along with enucleation of the left eye and the patient was started on intravenous Amphotericin B and her blood sugar levels were continuously monitored.

| Figure 2 :Smear of nasal biopsy showing aseptate hyphae (H and E, ×400)

Click here to view |

| Figure 3 :GMS-stained smears showing brown distorted, broad, aseptate hyphae characteristic of mucormycosis (×1000)

Click here to view |

Biopsy samples were also taken for culture and were inoculated on Sabouraud’s Dextrose agar (SDA), with and without actidione. After 48 h of incubation, luxurious cottony white growth typical of mucormycosis was observed. Lactophenol Cotton Blue (LPCB) was done from the growth on SDA which showed aseptate hyphae, collapsed sporangium and rhizoids just beneath the point where sporangiophore was present [Figure 4], suggestive of Rhizopus species. The repeated biopsy samples of the nasal mucosal showed similar findings.

| Figure 4 :LPCB preparation from growth on SDA showing collapsed sporangium and rhizoids characteristic of Rhizopus species.

Click here to view |

Meanwhile the patient responded well to the treatment, with subsidence of headache, nasal discharge and nasal bleeding.

The patient was discharged on oral Voriconazole, after a treatment of one month, during which the blood sugar levels were monitored stringently and the patient was left with the impairment of vision of left eye but without any residual neurological deficit.

| Discussion |

Infection with zygomycetic fungi is a well-recognized entity and occurs in persons with underlying disorders of various types, such as diabetes mellitus, hematological malignancies, severe malnutrition, chronic renal failure, chronic hepatic disease or immunodeficiency disorders. The most common predisposing factor for zygomycosis is diabetes mellitus since glucose and low pH enhance fungal invasion and growth. This is due to the hampering of the host phagocytosis and mobilization of polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Rhizopus and other Mucorales thrive on high glucose and acidic conditions. Cutaneous infections account for 16% of all forms of zygomycosis with associated mortality of 16%, compared to 67% for rhino-orbito-cerebral, 83% for primary pulmonary disease and 100% for disseminated disease. [4]

The most common organisms are Rhizopus species, although others like Absidia, Mucor are also frequently seen, whereas Saksenaea vasiformis and Apophysomyces elegans are rare pathogens. [3] These organisms are found in the soil and are important in the decay of organic materials. Humans are frequently exposed to the spores of these fungi, which ordinarily have little intrinsic pathogenicity. Sporulation and growth requires host defenses to be compromised and some debilitating illness is identified in over 95% of cases, like diabetes mellitus as seen in the present case. [5] Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis occurs after inhalation and deposition of spores on the nasal turbinates. The infection extends to adjacent paranasal sinuses. It may then progress through ethmoids and retroorbital tissues to eventually reach the brain through the orbital apex, as happened in the present case. [1],[2],[3],[4]

The most common clinical findings are headache, nasal discharge, epistaxis, followed by restriction of ocular movements, proptosis, ptosis and periorbital cellulites. Loss of functions of the third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves is most commonly reported. [4] In the present case, the patient presented with left third nerve palsy.

The prognosis of mucormycosis has improved markedly in the last 30 years. [4] Most of the diagnoses before the 1970s were made postmortem, but survival rates have increased as much as 89% in diabetics treated with surgery and Amphotericin B. [6] In the case reported here the patient responded to the surgical debridement and Amphotericin B therapy.

| References |

| 1. | Rinaldi MG. Zygomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1989;3:19-37. |

| 2. | Parfrey NA. Improved diagnosis and prognosis of mucormycosis: A clinicopathological study of 33 cases. Medicine 1986;65:113-23. |

| 3. | Sugar AM. Mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis 1992;14:126-9. |

| 4. | Shetty S, Hasan S, Kini U, Battu RR, Chang G, Muralidharan. Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis- an update Ind J Med Microbiol 2000;17:98-105. |

| 5. | Hill H. Infections. In: Cunnings CW, editor. Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. St. Louis: Mosby CV; 1986. p. 585-609. |

| 6. | Ferguson BJ. Mucormycosis of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngo Clin North Am 2000;33:349-65. |

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

| Check |

DOI: 10.4103/1755-6783.76180

| Figures |

[Figure 1], [Figure 2], [Figure 3], [Figure 4]