| Abstract |

Attaining universal health coverage (UHC) is a common aspiration for many countries across the world. We examine the term UHC in the existing literature, which could help the global community to achieve access to quality health services for all. The term “universal” necessitates aiming for equity to urge the country to provide quality health services, especially to those who are currently unreached. Likewise, the term “health” must focus on social determinants and express an individual’s perceived need without any harm to individual values and belief systems. The term “coverage” must make the transition from a measurement of access to quality in terms of coverage, appropriateness of care, and service utilization. Therefore, UHC, one of the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), involves health targets that must be redesigned and unpacked with doubled governmental efforts to strengthen primary healthcare, the close-to-client service for equitable health outcomes.

Keywords: Health equity, social determinants, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), universal health coverage (UHC)

| How to cite this article: Behera MR, Behera D. A critical analysis of the term “universal health coverage” under post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals. Ann Trop Med Public Health 2015;8:155-8 |

| Introduction |

At this point, in the 21st century, around 1 billion people across the world have not yet received quality health services or ever seen a doctor. [1] Further, nearly 100 million people are entering the category of “below poverty line” each year because they have been trapped into loans and selling assets to pay the booming healthcare expenditures in order to remain healthy and productive. [1] Many times, we see that governments have acknowledged the provision of the highest standard of health to its citizens; however, these have become luxuries and are only available to those who can afford them. Today, the provision of quality health services is possible through universal health coverage (UHC), a new international agreement within the global community that would commit to achieve quality health services for all.

The latest United Nations (UN) General Assembly resolution aimed to achieve UHC for the provision of affordable healthcare for poor and disadvantaged families. [2] However, UHC can be achieved if a clear understanding of UHC is framed and disseminated to the international community. If not, UHC could suffer the same fate as “Health for All,” which was ambiguously defined by the Alma Ata declaration in 1978 and gained a high level of political attention and support but failed to fulfill its goal by 2000 AD and even now. The main cause of such a failure has been identified as insufficient policy dissemination and profound variations in budgeting support around the globe. UHC is referred to by many names in the literature, such as “universal health-care coverage,” “universal health care,” or “universal coverage,” [3],[4] but in this text, we use UHC to mean “universal health coverage.” This clear meaning of UHC stands as an important landmark for a global understanding that would entail and provide a diverse, well-maintained framework to guide planners and policymakers in the achievement of equity in healthcare services and outcomes.

If UHC is wrongly understood, then it may lead to unintended policy results. UHC is often seen as an expansion of service provision and a way of financing health to remove barriers to access. However, the exact notion of UHC as it was adopted in the UN General Assembly resolution in its 2005 World Health Assembly resolution background paper was stated to be “access to key promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health interventions for all at an affordable cost, thereby achieving equity in access.” [5] This definition appears to indicate that equity is the backbone of UHC policy implementation. However, experiences from different countries show that the way equity has been addressed through different methods and procedures under UHC policies seems to be conditional, depending on how different countries define, plan, design, and implement UHC terms and policies. [6],[7]

What is immediately needed is the establishment of an empirical framework that will explicitly define each word in “UHC.” This would help provide practical solutions in terms of what UHC policy can achieve and deliver to measure national strategies and progress. If this were to fail, then probably important considerations for UHC policy outcomes would remain unresolved. Therefore, we suggest describing each term of UHC under this framework: “universal,” “health,” and “coverage.” This would assist countries in limiting wrong interpretations of UHC and help the global community to accept one meaning of UHC. Otherwise, the uncertainty that has clouded UHC will remain, making it more difficult to achieve the objectives of UHC policies.

Description of “universal”

The first term “universal” is defined as “a state responsibility to provide health care to all its citizens with specific emphasis of inclusion of all excluded and disadvantaged families.” [8] The term “universal” may sound noble; however, it might require a little change in policies, as some countries often deny provision of services to their own peoples, mostly unregistered migrants, refugees, nomadic populations, and those denied birth registration within national boundaries. These groups are often viewed by state administrators as being without legal entitlements, which are taken as reasons for the denial of access to healthcare. [9] Additionally, some other groups are purposefully discriminated against on the basis of their caste, color, disability, sex, ethnic origin, or religious identity. For example, being female or being a member of an ethnic minority or a religious community can be reasons for being barred from access to health and other government services which are even applicable for legal citizens. [10] If UHC aims to be realistic, then concerted efforts might result in defining how global aspirations for health can be met and how a state understands the concept of its citizenship and delivers targets toward the achievement of various responsibilities under UHC.

Description of “health”

The term “health” marks another much-argued topic of discussion. The UN General Assembly resolution brings a wider approach, broadening the definition of health from that of the simple provision of essential or basic health services. The UN mentions that UHC and social health insurance help in providing equitable access to health for the “highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” including “the work on social determinants of health.” [2] It is highly appreciated by nongovernmental organizations as it is important to realize that UHC targets might help in building a national consensus on social determinants, which would bridge the gaps and address concerns of health inequities and engage in more actions beyond the health sector. [11]

However, progress toward UHC in most countries can be seen as the delivery of basic or essential health services to their respective populations, especially to those who are employed in the private and public sectors as a starting point. [12] This approach, however, has often amplified inequities, as these sections of people have more access to health services than do poor and informal workers. [13] Bridging these inequities requires country-specific learning experiences and innovative strategies to successfully address the wider meaning of health. These experiences indicate that UHC policies might need, at a minimum, a comprehensive social health platform that would guarantee a continuum of care for every individual throughout their lifespan. It would encompass both communicable and noncommunicable disease and other policies, mainly childhood nutrition and education, occupational health, after-retirement health insurance plans, and traditional health systems for some countries. [14] Such a strategy would provide an opportunity to other sectors and ministries to realize that health is a primary concern for them. Further, issues such as to what degree UHC policies will act to address health inequities, how much of UHC policies should be addressed, and whether other sectors will participate or not demand urgent attention and full clarity of diagnosis.

Description of “coverage”

The debate on the term “coverage” is focused on the accessibility of services, including the measurement of effective service utilization. [15] “Coverage” also typically includes essential health services; however, appropriateness of care and quality of service in terms of coverage are the two aspects that should be the basic foundations for UHC to be effective. “Appropriateness of care” requires careful thought at the time of implementation because many countries experience an underinvestment in preventive and promotive approaches, lack of detailed attention to risk factors, and pervasive incentives demanded by service providers. [16] Similarly, the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) definition of UHC mentions the promotion of quality services but is silent in terms of any specific and practical guidelines about the quality needed in the achievement of coverage to avoid preventable deaths and ailments. [17]

Each term that is a part of “UHC” would be described imprecisely and obstruct discussion if these terms are not clearly defined. Key questions are to be asked on UHC policy, mainly: Who should be the target group under UHC, for which services they would be included, what level of quality of care they would receive, and to what extent equity outcomes can be made. If the meaning of “universal” indicates that every person will ultimately get advantages from UHC, then the currently unserved population will become the end users to reap benefits, creating more inequities that could further exacerbate the situation. Also, simply allocating policies and strategies to UHC, then scaling, cannot solve the reversal in health inequities among unserved/undeserved populations; pro-equity in origin, design, and planning; and ready for implementation. [18] The need of the hour is the active engagement of civil social organizations and strong political commitment that will harness accountability and promote a rights-based approach to meet the exact needs of poor and disadvantaged families. [19]

Reflection on Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

Fifteen years ago, 189 countries signed on for the MDGs that provide a pathway to eradicate extreme poverty and promote global development by 2015. Much has been achieved during these years; [1] however, there are also lessons to translate some imprecise goals into objectives and various approaches. The biggest challenges for MDG-targeting countries relate to the provision and sustenance of financial access for the improvement in service quality, especially for the poor. This led UHC policies to worsen, rather than reduce, inequities and disparities. [20] Another lesson learned from MDGs is that there has been a slow rate of uptake and acceptance, partly due to the lack of a participatory process at the beginning. If UHC must be effective, then it must be unpacked with measurable subtargets, which is feasible for achieving and indicating governments, coalitions, partners, and for each individual of each country to realize that UHC benefits them by reducing inequalities in health outcomes. Further, clarity on each term of UHC is absolutely needed, as it will bring a wide range of opportunities for stakeholders to participate in various meetings and conferences and to shape national goals. It is also very important to know what UHC is not. This will help in stemming risks and threats to UHC and to provide a regulatory, standard approach to understand what exactly UHC is meant for. Additionally, continuous dialogue on UHC can prompt the planners and decision-makers to look into any potential distributive effects in UHC policies that can substantially reduce rich-poor gaps.

Implementation of UHC in different countries

Today, various countries are implementing UHC on their own terms. The question is, is this due to confusion or is UHC an aspirational slogan for local reality? In China, the most recent form of UHC is Quanmin Jiankang Fugai (“health coverage for all”). In Portugal, Cobertura universal emsaude exists as a form of UHC that deals with narrowing health inequalities. In the Philippines, Kalusugan Pangkalahatan (“health for all”) is used for UHC and it is intended to improve access to services for the poor. In France, UHC is synonymous with Coverture Maladie Universelle (“universal disease coverage”), which highlights the burden of disease in that country, mainly human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis, and malaria. [21] Further, how the global community might see and define various elements of UHC for inclusiveness and appropriateness also poses questions. The recent study in Lancet from 14 countries and 1 province, Punjab, in Pakistan demonstrated that inequity in a particular country is possible when an output-based equity-focused approach is taken. [22] This analysis tried to explain the reasons for poor service utilization, poor quality coverage, low access, and inappropriateness in healthcare, and enable national and subnational planners and policymakers to understand them. [23] Thus, innovations, lessons, and evidences regarding MDGs can contribute meaningfully to the countries, where they can look for practical solutions and policies to implement with the realization that the UHC dream can be achieved. The term “universal” necessitates aiming for equity to urge the country to provide equitable health outcomes, especially to those who are currently unreached and ostracized from the mainstream. Likewise, the term “health” must focus on social determinants, express individuals’ perceived needs without any harm to individual values and belief systems, and find out ways in which actions can be made and implemented beyond the health sector. The term “coverage” must make the transition from involving the measurement of access to quality in terms of coverage, appropriateness of care, and service utilization. Above all, the most crucial point is to build strong commitment and involve the participation of all sectors starting from civil society to private bodies with government and development agencies to ascertain the true consensus on the meaning of UHC within countries. This will lend immense confidence in designing country-specific evidence-based interventions toward delivering and achieving UHC.

| Conclusion |

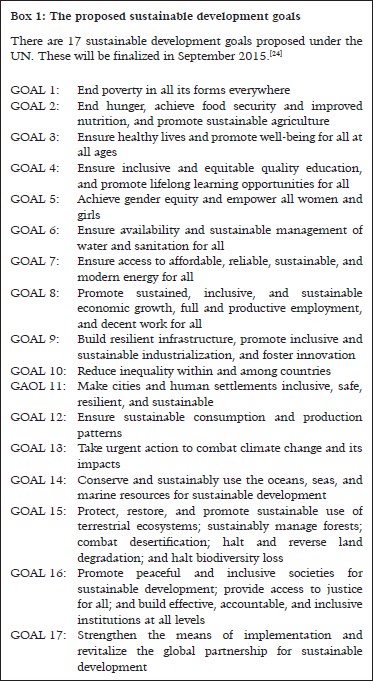

At present, MDGs are due for expiration at the end of 2015, and as a result the name post-2015-Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will be used. All health-related goals under MDGs will be placed under the SDGs along with 17 newer targets [Box 1]. The SDGs are to be finalized by September 2015 by the largest UN consultation process and dialogue. Among the proposed SDGs currently available, UHC stands as one among 13 indicators toward the achievement of SDGs. Therefore, we welcome UHC for much inclusive and broader discussion under post-2015 SDGs that could help in establishing pro-equity UHC indicators for the achievement of UHC. To maximize UHC benefits and obtain favorable outcomes under post-2015 SDGs truly requires a global consensus and a precise, well-placed operational framework. Such a framework must be built on lessons learned from MDGs that would demystify UHC and encourage planners and policymakers to track and monitor UHC progress under post-2015 SDGs.[24]

| References |

| 1. |

World Health Organization [WHO]. World Health Report 2010. Health systems financing: The path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

|

| 2. |

United Nations General Assembly. Agenda item 123. Global health and foreign policy, A/67/L36. 67 th United Nations General Assembly. New York, NY, USA; 2012.

|

| 3. |

George M. Viewpoint: Re-instating a ′public health′ system under universal health care in India. J Public Health Policy 2015;36:15-23.

|

| 4. |

Mills A, Ataguba JE, Akazili J, Borghi J, Garshong B, Makawia S, et al. Equity in financing and use of health care in Ghana, South Africa and Tanzania: Implications for paths to universal coverage. Lancet 2012;380:126-33.

|

| 5. |

World Health Assembly. Social health insurance: Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance: Report by the secretariat. 58 th World Health Assembly; Geneva, Switzerland; 2005.

|

| 6. |

Kutzin J. Anything goes on the path to universal health coverage? No. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:867-8.

|

| 7. |

Gwatkin DR, Ergo A. Universal health coverage: Friend or foe of health equity? Lancet 2011;377:2160-1.

|

| 8. |

Kirby M. The right to health fifty years on: Still skeptical? Health Hum Rights 1999;4:6-25.

|

| 9. |

Kingston LN, Cohen EF, Morley CP. Debate: Limitations on universality: The ′right to health′ and the necessity of legal nationality. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2010;10:11.

|

| 10. |

Open Society Justice Initiative. Committee on the elimination of racial discrimination: Submission for the review. Kenya; 2011.

|

| 11. |

Ooms G, Brolan C, Eggermont N, Eide A, Flores W, Forman L, et al. Universal health coverage anchored in the right to health. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:2-2A.

|

| 12. |

Ekman B, Pathmanathan I, Liljestrand J. Integrating health interventions for women, newborn babies, and children: A framework for action. Lancet 2008;372:990-1000.

|

| 13. |

Carrin G, Mathauer I, Xu K, Evans DB. Universal coverage of health services: Tailoring its implementation. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:857-63.

|

| 14. |

Lang T, Kaminski M, Leclerc A. Report of the WHO commission on social determinants of health: A French perspective. Eur J Public Health 2009;19:133-5.

|

| 15. |

Frenz P, Vega J. Universal coverage with equity: What we know, don′t know and need to know. First Global Symposium on Health Systems Research. Montreux, Switzerland; 2010.

|

| 16. |

O′Connell T. National health insurance in Asia and Africa: Advancing equitable social health protection to achieve universal health coverage. New York: UNICEF; 2012.

|

| 17. |

Vega J. Universal health coverage: The post-2015 development agenda. Lancet 2013;381:179-80.

|

| 18. |

Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generator: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health organization; 2008.

|

| 19. |

Rasanathan K, Norenhag J, Valentine N. Realizing human rights-based approaches for action on the social determinants of health. Health Hum Rights 2010;12:49-59.

|

| 20. |

UNICEF. Progress for children: Achieving the MDGs with equity (No. 9). New York: UNICEF; 2010.

|

| 21. |

Bermejo RA, Xu J, Henao DE, Ho BL, Sieleunou I. What does UHC mean? Lancet 2014;383:951.

|

| 22. |

Carrera C, Azrack A, Begkoyian G, Pfaffmann J, Ribaira E, O′Connell T, et al.; UNICEF Equity in Child Survival, Health and Nutrition Analysis Team. The comparative cost-effectiveness of an equity-focused approach to child survival, health, and nutrition: A modelling approach. Lancet 2012;380:1341-51.

|

| 23. |

Chopra M, Sharkey A, Dalmiya N, Anthony D, Binkin N; UNICEF Equity in Child Survival, Health and Nutrition Analysis Team. Strategies to improve health coverage and narrow the quality gap in child survival, health, and nutrition. Lancet 2012;380:1331-40.

|

| 24. |

Open Working Group Proposal for Sustainable Development Goals. Available from: http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1579SDGs%20Proposal.pdf. [Last accessed on 2015 May 1].

|

Source of Support: None, Conflict of Interest: None

| Check |

DOI: 10.4103/1755-6783.162660